It was a beautiful day in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, but in front of us the skies were darkening.

A fitful wind blew, and people at the local gas station talked of a line of severe storms on the way.

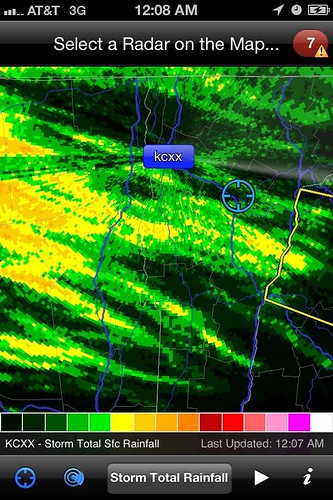

I slowly pulled up the radar on my phone, through a spotty Internet connection, and checked out the line of storms.

(radar accessed using

RadarScope app. At $9.99 it's a bit too expensive for the general public but for people as obsessed with the weather as I access to the many new NEXRAD radar products is indispensable)

The line of storms indeed looked nasty, but was moving slowly. Waiting it out would probably mean losing the rest of the day. It seemed that there was a gap in the line along our path, so we decided to drive through the storm.

As we started driving into the squall line, the clouds lowered. At one point they were CHURNING in an incredibly ominous way - instead of the motionless mammatus clouds near many severe thunderstorms, these throbbed and rolled like a sheet in the wind.

There didn't appear to be any rotation of the sort that would form tornados, but to the north, where the storm was more severe, the sky turned a sickly green color - the type of color that seems to be reserved for the the most severe storms rolling off of the Great Plains. This color is almost never seen in Vermont, pretty unheard of in California, and is very bad news. I began to wonder if we were making a mistake.

Needless to say we made it through the storm safely. The wind was not severe, nor was there hail, but there was drenching rain. The rain was not particularly unusual for a severe thunderstorm, except that the line of storms was barely moving forward. At least driving through the storm we could get out the other side.

When we finally reached the western side of the storm, in the Bad River Reservation of Wisconsin, we stopped at a store where we encountered a leaky roof and news of rising rivers. Several roads were closed, and just outside the store a culvert was belching forth muddy water at full capacity, with a concerned engineer looking on. The town just beyond was experiencing storm drain overflow and street flooding. The rivers we crossed were absolutely raging, and as we drove southwest the rest of the way to Minneapolis we encountered scattered occasionally heavy rain and frequent lightning to the west and above us. The line of storms was still barely moving.

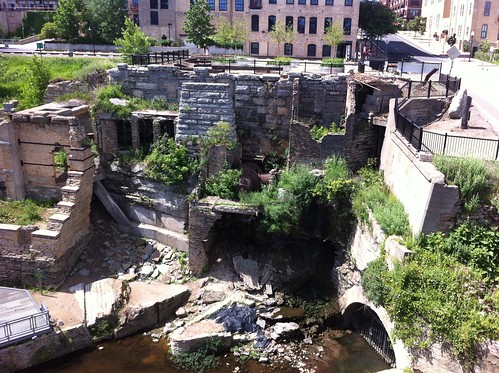

As it turns out, the storms had passed slowly through Duluth earlier that day.

The storms completely drenched the area, dropping as much as 10 inches of rain and causing catastrophic flooding, seemingly comparable on a local scale to what Vermont experienced in Tropical Storm Irene. In short, a catastrophe, and a complete failure of the aging and obsolete runoff control structures in the city.

About two weeks later we were enjoying a 4th of july dinner with new friends in Montpelier. It was a hot, muggy day, and mammatus clouds (of the more stationary sort) again hovered overhead. Distant thunder rumbled, but one lightning bolt smashed down apparently in downtown Montpelier despite the storm still being closer to Burlington (perhaps a positive bolt out of the anvil?). Thankfully, we were safe in an enclosed porch area. According to the radar, Burlington was getting hammered but the storm was going to pass just south of Montpelier.

Then, to the south, I noticed a low, roiling line of extremely fast-moving clouds. Behind them the sky was slate-grey, but with just a hint of green. The line of clouds was moving towards us fast and unexpectedly - sign of a gust front. After just a few minutes the clouds raced directly overhead and the gust of wind hit. A swirling wind came up straight out of the south (the prevailing wind direction had been northwest), quickly rising to perhaps 50 or 60 miles per hour. With it came sheets of rain blown out of the storm to the south. The wind was gone as fast as it came, but as it wound down we heard a loud pop and saw smoke rising across the river. With it was a flicker of flame or sparks and an odd burnt smell. I immediately called 911 to report the fire. We later learned that it was caused by a large maple tree falling across power lines. Thankfully the fire did not spread, and crews quickly deactivated the power lines.

As the storm moved off to the east, it maintained its intensity, and the towering clouds caught the light of the setting sun. The scene was beautiful, and even more impressive in person as the departing storm flickered with frequent lightning.

What we experienced, again, was the edge of a storm. Aside from the one maple tree, Montpelier did not sustain serious damage that I am aware of. In Burlington, it was a whole other story. A 'bow echo' line of thunderstorms scored a direct hit on the Old North End and downtown sections of Burlington. The city experienced sustained 60 to 70 mile per hour winds that brought down numerous trees, and up to two inches of rain in a very short amount of time. The branches brought down by the wind immediately clogged culverts, and the water had nowhere to go. Soon several areas of the city were flooded with waist-deep dirty water.

Above: storm damage to trees along Pearl Street/Colchester Avenue in Burlington

The Burlington storm wasn't quite as wet as the Duluth storm, but the winds made for a storm that will be remembered for quite some time. There's been a lot of talk linking these storms to climate change, but it's important to remember that storms like this are not all that uncommon in Vermont. They just generally hit sparsely populated areas, because most of vermont is sparsely populated. This storm will be remembered not only because of its severity, but because it hit the largest city of Vermont and struck a glancing blow on the state capitol on the Fourth of July (thankfully, Montpelier's parade and festival was held on the 3rd this year). The extensive damage of this storm would have only been of note to foresters, ecologists, and perhaps a few farmers if it occurred in many parts of Vermont.

On the other hand, there's been a very intense heat wave over much of the country, and both of these storms formed on the edge of the heat wave area - a place where severe thunderstorms often form in midsummer. If climate change caused the heat wave to become more severe, perhaps it caused the storms to become more severe as well.

The storms also highlight the need for better flood and runoff management in our cities and towns. The Duluth flood was made much worse by aging infastructure. The Burlington flood largely struck areas

along a historic stream channel that is now routed underground (see light blue line) - but unfortunately is unlikely to be a candidate for 'daylighting' as it passes through the densest part of the city. I don't think rain gardens, empty rain barrels, pervious pavement, and other 'slow water' measures would have completely stopped the floods, and they certainly wouldn't have decreased the wind that damaged so many trees in Burlington. However, the weather before this storm had been quite dry, and those measures probably would have done a good job of decreasing the magnitude of the flood and its associated damage.