Even though Sandy's remnants are still spinning down and the Midatlantic is only beginning its cleanup from the storm, people are already starting to talk about whether or not human-caused climate change may have created or worsened the storm. I'm not going to cover the topic in depth, but there are a few things worthy of mention here.

First of all, Sandy was a huge storm, a monster created when a hurricane merged with an extratropical storm. This scenario can lead to some of the largest and most intense storms our planet can experience - storms that combine the hot, wet tropical energy of a hurricane with the battling air masses of the mid latitudes.

This is not the first time such a storm has formed. They have ranged in the Atlantic and the Pacific before, and as far as I know can occur in the Southern Hemisphere as well. Sandy was a monster, but was it our creation? Not necessarily. Sandy passed over the warm Gulf Stream, which is warmer than usual right now, and this may have strengthened the storm a bit. But even without this factor, Sandy would have been a very severe storm.

There's more, though. A monster isn't defined just by what it is, but what it DOES. Extratropical storms, even the huge ones, almost always move from west to east. Had Sandy curved to the east, like so many other storms, it would have spent its wrath over the ocean. Perhaps Sandy would have hit Newfoundland like the Perfect Storm, or could have crossed the ocean and hit Europe, but at that time the storm probably would have been weaker.

Sandy, on the other hand, turned west. This was surprisingly well-forecast by computer models, and was caused by a deep meander in the atmospheric river we call the jet stream. Erratic hurricane paths are not uncommon, and the 1938 hurricane followed a somewhat similar one. The jet stream pattern was nevertheless quite unusual. It's one we've seen before, though. I wrote about it almost two years ago in the second most viewed post on this blog. Lack of Arctic sea ice may make that weather pattern more common.

The quick summary? The jet stream rotates around the North Pole both because of the Coreolis Effect and because the North Pole is the coldest spot in the hemisphere... or at least it was. For most of the last few centuries (and perhaps since the last Ice Age) the Arctic Ocean has been frozen. The thick ice allowed the air to become incredibly frigid. Lately there has been very little sea ice. Liquid is an incredible moderator of temperature, and an Arctic Ocean with open water tends to moderate the winter temperatures upwards towards the freezing point, because it can't get more than a few degrees below freezing (salt, of course, decreases the freezing temperature of water). The Arctic Ocean is then perhaps less cold than Canada, Siberia, and Greenland. So, the jet stream shifts south around those continents, and orbits around the new 'poles of cold' in the continental center. This could lead to increased wandering in the atmospheric river... the kind that could grab a monster from the Atlantic and pull it right into the most populated part of the Eastern US coastline.

Jeff Masters does a good job of describing this in more detail here.

This is all new science of course. We don't know anything for sure. It's a bit scary though.

The hurricane season is winding down so we probably won't have to worry about any more hurricanes being ingested by nor'easters this year. The pattern may, however, lead to a brutal winter in the Northeast this year. Less sea ice doesn't warm New England all that much, it will still be plenty cold enough to snow, and we may have to deal with more storms than usual.

Or maybe not. Last winter was a non-event here.

What do you think? I'd love to hear any thoughts on the science and what the future may hold. Please keep to the science though. I know people like to argue about global warming on the Internet, and it's fine to have a debate if you can back up your claims, but I'm gonna delete any 'GLOBAL WARMING IS A LIBERAL HOAX' posts, or anything about HAARP or chemtrails (if you don't know, don't ask. You don't want to know.)

Thursday, November 1, 2012

Tuesday, October 30, 2012

Mini-Update: Sandy Spares Vermont but Not Mid-Atlantic

We awoke this morning to the sound of raindrops and gusty winds. Just the sort of weather you'd expect in late October. No hurricane winds, just enough wind to blow the rain against the window.

As I look online and hear from friends, it looks like Vermont was mostly spared Sandy's damage. There are a few trees down and a few power outages. But hear in Montpelier, if I didn't know what was happening elsewhere, the only thing odd I would have noticed was the odd clouds and the much warmer rain than usual. Yesterday was actually a somewhat nice day.

My heart goes out to those in the Midatlantic and other areas that were affected by this storm. There will be much, much more to say about Sandy in the future, but for now, I'm just thankful we were spared this time. After what happened in Irene we would not have done well with another disaster.

Matt Sutkoski of the Weather Rapport blog (from the Burlington Free Press) has pointed out that the White Mountains may have also shielded us from much of the rain and wind. Mount Washington picked up a 140 mph wind gust! The complex topography of Vermont makes rain and especially wind hard to predict. During Irene, East Middlebury had almost no wind and the rain, while heavy, was not catastrophic. Little did we know the rdige behind our home had picked up around 10 inches of rain in less than 24 hours... at least we didn't know until the river came through town.

Best of luck out there.

As I look online and hear from friends, it looks like Vermont was mostly spared Sandy's damage. There are a few trees down and a few power outages. But hear in Montpelier, if I didn't know what was happening elsewhere, the only thing odd I would have noticed was the odd clouds and the much warmer rain than usual. Yesterday was actually a somewhat nice day.

My heart goes out to those in the Midatlantic and other areas that were affected by this storm. There will be much, much more to say about Sandy in the future, but for now, I'm just thankful we were spared this time. After what happened in Irene we would not have done well with another disaster.

Matt Sutkoski of the Weather Rapport blog (from the Burlington Free Press) has pointed out that the White Mountains may have also shielded us from much of the rain and wind. Mount Washington picked up a 140 mph wind gust! The complex topography of Vermont makes rain and especially wind hard to predict. During Irene, East Middlebury had almost no wind and the rain, while heavy, was not catastrophic. Little did we know the rdige behind our home had picked up around 10 inches of rain in less than 24 hours... at least we didn't know until the river came through town.

Best of luck out there.

Sunday, October 28, 2012

Hurricane Sandy Bears Down on East Coast

It feels good to be home in Vermont.

This weekend we were in New York City for a wedding. It was great to attend the wedding and see frields, but being in one of the world's largest cities while it awaited a massive storm was an odd experience.

People were going about their business yesterday, but they were talking. Some said it would be no big deal. Others were worried. No one really knew, of course. Sandy is following a track different from other storms that we know of, so even the experts watching the storm aren't sure what is to come. Online, people argued and bickered as they often do, with some dismissing the storm as insignificant, and others making ridiculous doomsday predictions. Some people even posted comments about this being the biggest storm that 'ever existed' - very unlikely considering the multi-billion year history of our planet's atmosphere. It's not the biggest storm ever.. but it is a big, weird, scary storm.

Last night I didn't get much sleep, for a variety of reasons. I laid and listened on an air mattress to the whistling of a breeze outside the window while sirens wailed. In most parts of Vermont you don't hear all that many sirens, though they were common in California where I grew up. I wondered if these New York sirens were related to drunken halloween party revelers... or to an early arrival of Sandy. As I drifted in and out of sleep, I wondered if the storm had come early and we would be trapped in NYC for the next few days. I wondered what the hurricane-force winds would look and sound like as they raged through the manmade canyons of Manhattan. Amidst fitful dreams I realized that if the subways filled with water, millions of rats would be forced to the surface during the storm.

It's a strange and hollow feeling being so far from home in the face of something so immense and unpredictable. During Irene we had to leave our home, and I spent a sleepless night wondering if we would find it gone in the morning. Before Sandy I had a sleepless night wondering how I would GET home.

Thankfully, the morning dawned cool and breezy and overcast, but with no hurricane. (There was really no way the storm could have gotten there so fast, but such things are hard to realize when half asleep). The subways were still running at that time (as of now they are closed.) We were able to catch our bus home, and moving north we outpaced the spreading, torn low clouds.

It's difficult to say what awaits New York City and the other big coastal cities, but confidence is building that a possibly historic storm surge will occur, and that the disruptions will be massive. This won't be like Katrina - New York City is not below sea level, for one thing, and the evacuation areas are narrow and can be walked out of. But the economic impacts of this storm will be large, and unfortunately it is likely that some people will lose their lives due to not taking the storm seriously or just to bad luck.

The wind is expected to be lighter here, but not by much - wind gusts above 60 miles per hour are not out of the question in Montpelier tomorrow night, with the peaks seeing gusts well over 80 mph. The wind will be a bit lighter in Burlington, but still significant. East Middlebury and other towns just west of the Green Mountains may experience locally stronger downsloping winds - perhaps over 70 mph.

This evening the clouds looked like a sheet blowing in a strong wind...

We've got quite a storm to get through here, but I do feel safer being at home. I'd better get some sleep tonight though. Tomorrow night the windows will be rattling, tree branches will be snapping... it will be another night of restless dreams and little sleep.

This weekend we were in New York City for a wedding. It was great to attend the wedding and see frields, but being in one of the world's largest cities while it awaited a massive storm was an odd experience.

People were going about their business yesterday, but they were talking. Some said it would be no big deal. Others were worried. No one really knew, of course. Sandy is following a track different from other storms that we know of, so even the experts watching the storm aren't sure what is to come. Online, people argued and bickered as they often do, with some dismissing the storm as insignificant, and others making ridiculous doomsday predictions. Some people even posted comments about this being the biggest storm that 'ever existed' - very unlikely considering the multi-billion year history of our planet's atmosphere. It's not the biggest storm ever.. but it is a big, weird, scary storm.

Last night I didn't get much sleep, for a variety of reasons. I laid and listened on an air mattress to the whistling of a breeze outside the window while sirens wailed. In most parts of Vermont you don't hear all that many sirens, though they were common in California where I grew up. I wondered if these New York sirens were related to drunken halloween party revelers... or to an early arrival of Sandy. As I drifted in and out of sleep, I wondered if the storm had come early and we would be trapped in NYC for the next few days. I wondered what the hurricane-force winds would look and sound like as they raged through the manmade canyons of Manhattan. Amidst fitful dreams I realized that if the subways filled with water, millions of rats would be forced to the surface during the storm.

It's a strange and hollow feeling being so far from home in the face of something so immense and unpredictable. During Irene we had to leave our home, and I spent a sleepless night wondering if we would find it gone in the morning. Before Sandy I had a sleepless night wondering how I would GET home.

Thankfully, the morning dawned cool and breezy and overcast, but with no hurricane. (There was really no way the storm could have gotten there so fast, but such things are hard to realize when half asleep). The subways were still running at that time (as of now they are closed.) We were able to catch our bus home, and moving north we outpaced the spreading, torn low clouds.

It's difficult to say what awaits New York City and the other big coastal cities, but confidence is building that a possibly historic storm surge will occur, and that the disruptions will be massive. This won't be like Katrina - New York City is not below sea level, for one thing, and the evacuation areas are narrow and can be walked out of. But the economic impacts of this storm will be large, and unfortunately it is likely that some people will lose their lives due to not taking the storm seriously or just to bad luck.

The wind is expected to be lighter here, but not by much - wind gusts above 60 miles per hour are not out of the question in Montpelier tomorrow night, with the peaks seeing gusts well over 80 mph. The wind will be a bit lighter in Burlington, but still significant. East Middlebury and other towns just west of the Green Mountains may experience locally stronger downsloping winds - perhaps over 70 mph.

This evening the clouds looked like a sheet blowing in a strong wind...

We've got quite a storm to get through here, but I do feel safer being at home. I'd better get some sleep tonight though. Tomorrow night the windows will be rattling, tree branches will be snapping... it will be another night of restless dreams and little sleep.

Tuesday, October 23, 2012

A Tale of Two Models: Will A Major Storm Slam the East Coast Next Week?

Early next week in Vermont we may be experiencing a flooding downpour and raging winds. We may be experiencing fair skies, or some light drizzle. We could even be slammed by a major blizzard. Right now there is significant potential for a major storm to impact the US Northeast and far eastern Canada... but there's also a good chance we'll have rather bland weather.

Why the uncertainty? Well, as is often the case, the computer models we use to forecast the weather don't agree on what will happen.

Tropical Storm Sandy has formed way south in the Caribbean, and is moving north. It will probably strengthen into a hurricane and cause damage in Cuba, Haiti, and the Bahamas, before continuing north. After this point...

The two main weather models that offer forecasts 8 days out are the ECMWF, or Euro, and the GFS.

Here's what the Euro forecasts for next Tuesday (from Wunderground):

Yikes! It actually looks a bit like a colder Irene. Though, it's important to note that it would be converting to an extratropical storm. It wouldn't still be a hurricane. This might mean a less rainy and windy storm, but also means:

Yep. That's snow. If this were exactly correct Baltimore could pick up some snow, and Buffalo would be buried. It won't be exactly right though, no matter what, because this is seven days away. If there is any snow, it could occur just about anywhere in the Northeast, but won't occur everywhere.

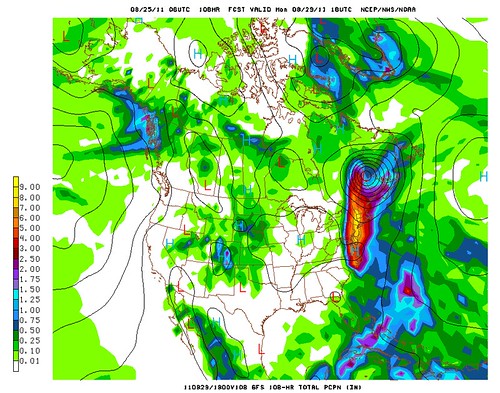

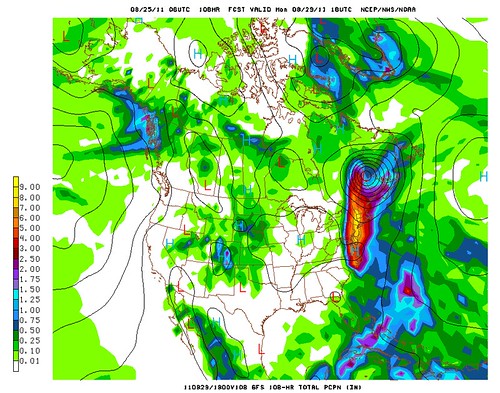

OK, so the Euro model forecasts a big storm. What does the GFS indicate?

No Nor'easter there. Northern Vermont might get some flurries, and northeastern Maine some heavy rain... but nothing extreme. Instead of forming into a nor'easter, Sandy would wander off to sea.

So which model, if any, will be correct? It's far too early to say. I think the Euro has been a bit more accurate than the GFS lately. Then again, the GFS pretty much nailed Irene's Vermont impacts over 100 hours before it happened. There's also a GFS 'ensemble' that runs a model several times with slightly varying starting conditions. About half of the ensemble members had the storm making landfall somewhere in the northeastern US, the other half had it going off to sea.

So either option is probably equally likely. If the storm does hit, the areas east of the low center would likely have the heaviest rain and strongest wind, while areas to the west would have the highest chance of picking up heavy snow. It's far too early to speculate where each could occur with any accuracy.

So... it's definitely not worth worrying about, but it's worth checking to make sure you have extra supplies and are prepared to weather a serious fall storm. This storm may miss, but it's nearly certain that a significant nor'easter will come up the coast at least once or twice this fall or winter, so it would be good to be prepared.

A hurricane combining with or turning into a nor'easter sounds a bit like science fiction, but it's happened in the past. Not surprisingly, it can result in a very serious storm that combines the wind and moisture of a hurricane with the vast size and wintry potential of a nor'easter. In 1804, the Snow Hurricane occurred when a hurricane converted to an extratropical storm and pulled in cold air on its northern and western sides, resulting in extremely heavy snow over most of New England in mid October. The Perfect Storm of 1991 was a hybrid between a hurricane and a nor'easter that formed when a nor'easter absorbed Hurricane Grace and then followed an unusual wandering path over the Gulf Stream. Incredibly, it actually formed a small new hurricane at its core, and became a monster storm that caused damage and loss of life along the US and Canadian East Coasts. Later it was remembered in the well-known movie describing the loss of a fishing boat that was unable to weather this storm.

Regardless of what happens next week, both the results of these computer models and a look back at these two intense winter storms remind us of the intensity and scope of storms that sometimes strike the eastern portion of North America.

Why the uncertainty? Well, as is often the case, the computer models we use to forecast the weather don't agree on what will happen.

Tropical Storm Sandy has formed way south in the Caribbean, and is moving north. It will probably strengthen into a hurricane and cause damage in Cuba, Haiti, and the Bahamas, before continuing north. After this point...

The two main weather models that offer forecasts 8 days out are the ECMWF, or Euro, and the GFS.

Here's what the Euro forecasts for next Tuesday (from Wunderground):

Yikes! It actually looks a bit like a colder Irene. Though, it's important to note that it would be converting to an extratropical storm. It wouldn't still be a hurricane. This might mean a less rainy and windy storm, but also means:

Yep. That's snow. If this were exactly correct Baltimore could pick up some snow, and Buffalo would be buried. It won't be exactly right though, no matter what, because this is seven days away. If there is any snow, it could occur just about anywhere in the Northeast, but won't occur everywhere.

OK, so the Euro model forecasts a big storm. What does the GFS indicate?

No Nor'easter there. Northern Vermont might get some flurries, and northeastern Maine some heavy rain... but nothing extreme. Instead of forming into a nor'easter, Sandy would wander off to sea.

So which model, if any, will be correct? It's far too early to say. I think the Euro has been a bit more accurate than the GFS lately. Then again, the GFS pretty much nailed Irene's Vermont impacts over 100 hours before it happened. There's also a GFS 'ensemble' that runs a model several times with slightly varying starting conditions. About half of the ensemble members had the storm making landfall somewhere in the northeastern US, the other half had it going off to sea.

So either option is probably equally likely. If the storm does hit, the areas east of the low center would likely have the heaviest rain and strongest wind, while areas to the west would have the highest chance of picking up heavy snow. It's far too early to speculate where each could occur with any accuracy.

So... it's definitely not worth worrying about, but it's worth checking to make sure you have extra supplies and are prepared to weather a serious fall storm. This storm may miss, but it's nearly certain that a significant nor'easter will come up the coast at least once or twice this fall or winter, so it would be good to be prepared.

A hurricane combining with or turning into a nor'easter sounds a bit like science fiction, but it's happened in the past. Not surprisingly, it can result in a very serious storm that combines the wind and moisture of a hurricane with the vast size and wintry potential of a nor'easter. In 1804, the Snow Hurricane occurred when a hurricane converted to an extratropical storm and pulled in cold air on its northern and western sides, resulting in extremely heavy snow over most of New England in mid October. The Perfect Storm of 1991 was a hybrid between a hurricane and a nor'easter that formed when a nor'easter absorbed Hurricane Grace and then followed an unusual wandering path over the Gulf Stream. Incredibly, it actually formed a small new hurricane at its core, and became a monster storm that caused damage and loss of life along the US and Canadian East Coasts. Later it was remembered in the well-known movie describing the loss of a fishing boat that was unable to weather this storm.

Regardless of what happens next week, both the results of these computer models and a look back at these two intense winter storms remind us of the intensity and scope of storms that sometimes strike the eastern portion of North America.

Tuesday, October 16, 2012

Cold Air that Flows like Water

As autumn deepens and moves towards winter, cold nights are becoming more common. We've already had one very hard freeze (last Friday night) when most areas of Vermont saw lows in the mid 20s or even colder. Aside from that, we've seen quite a few marginal frosty nights. Some areas have seen several hard freezes starting as early as mid September, while others, just like here in Montpelier, saw the growing season extend until last Friday when it abruptly ended.

Above: on October 9th, a heavy frost settled over most of the Northeast Kingdom, but not Montpelier, Plainfield, or Barre. These little plants are bedstraw (Galium).

The early season frosts seem a bit random, but they are anything but. We can't "see" temperature changes, although we can notice where frost occurs on marginal freeze nights. There's another way to see the patterns of cold air too - and it is by observing where plants occur on the landscape.

above: red spruce on a talus slope.

Most people have noticed that conifers, like pine and spruce, often occur on cold mountaintops. In Vermont, the most cold-tolerant trees are spruce, fir, paper and yellow birch, and aspen. Of these, the hardwoods are opportunistic and occur in other areas as well, but spruce and fir are almost entirely restricted to areas that get very, very cold - like the steep talus slope high on Umpire Mountain, seen above. Sometimes we also see spruce and fir in somewhat unexpected settings.

The picture above is an oblique, Google Earth view of a valley nestled between Umpire Mountain, Burke Mountain, and Kirby Ridge. The steepness of the terrain is exaggerated in this view. The Burke ski area is visible on the far side of Burke Mountain (center) while the spruce forest in the photo I posted earlier is on the far right of this view, on the steep slopes of Umpire Mountain. Not surprisingly, you can see lots of conifers on these tall mountains, where a lot of snow is also visible (the photo was taken in April of 2006).

You'll also notice something else here though. The conifers aren't restricted to the mountaintop. There are also a bunch of them in the valley. What gives?

Those spruce and fir trees are present in the valley bottom because of cold air drainage. Most of the time, the mountaintops are the coldest parts of Vermont. But, during a cold, still clear night, things change. Heat rapidly radiates away from the mountains, but as air cools, it sinks. Cold air is denser than warm air. Cold air from the mountains surrounding this little valley trickles down to the valley bottom, where it pools. This cold air is no joke. In fact, on a frigid night in 1933, the town of Bloomfield 18 miles to the northeast of this basin measured a low temperature of -50, tied with a more recent record in Maine for the coldest temperature ever recorded in New England. There aren't any weather stations in Victory Basin (the area described above) though, and I wouldn't be surprised if it was even colder there that night.

There aren't many trees that can stand up to -50 degree temperatures, but spruce is one of them. Together with fir and a few other species, the cold air pockets of New England and upstate New York support a natural community called Lowland Spruce-Fir Forest.

View Larger Map

The above map offers a view of Victory Basin, with the lowland spruce-fir forests and associated wetlands clearly visible (this is the same area where I saw a moose a few weeks ago). If you wander north on the above map you will notice a pattern of the darker green conifers being present both in the valleys and on the peaks. If you continue dragging the view north you will come to the Nulhegan Basin, an even larger cold-air drainage area. Both the Victory and Nulhegan basins support species similar to that in the boreal taigas in Canada, ranging from rhodora to the state endangered spruce grouse. Not surprisingly, moose are very abundant in these areas as well. Snowshoe hare and beaver are abundant, and it's possible that even lynx inhabit these icy forests.

Cold air drainage isn't limited to icy climates like Vermont's either. They play a part in the ecology and natural history of the sunny Santa Monica Mountains in Malibu, California as well. I've seen frozen ground and 'frost heaves' in this part of Malibu Creek State Park:

View Larger Map

This is just a few miles from the immediate coastline, where temperatures very rarely drop below 40F and hard freezes may only occur once or twice a century. Stephen Davis of Pepperdine University has found evidence that these cold air drainages strongly affect the vegetation in the area, and he has told me that single-digit (f) temperatures are not unheard of in these isolated areas. I believe it - one spring I lived in Park Service employee housing at nearby Rocky Oaks park, another cold air drainage area, and hard freezes were common on many clear nights well into April. I had to scrape the ice off of my car windshield in the mornings with a credit card because I didn't have an ice scraper. There were even areas of black ice on some of the nearby roads on cold nights after rainstorms.

Malibu's cold air pockets are more defined by an absence than a presence. The ubiquitous laurel sumac shrub that is found over almost all of the Santa Monica Mountains does not occur in cold air drainage areas. It is said that early farmers would only plant citrus where laurel sumac was growing, because it meant frost was very rare.

Next time you are in a small valley or hollow, look at the plants around you, because they may have an icy story to tell.

Above: on October 9th, a heavy frost settled over most of the Northeast Kingdom, but not Montpelier, Plainfield, or Barre. These little plants are bedstraw (Galium).

The early season frosts seem a bit random, but they are anything but. We can't "see" temperature changes, although we can notice where frost occurs on marginal freeze nights. There's another way to see the patterns of cold air too - and it is by observing where plants occur on the landscape.

above: red spruce on a talus slope.

Most people have noticed that conifers, like pine and spruce, often occur on cold mountaintops. In Vermont, the most cold-tolerant trees are spruce, fir, paper and yellow birch, and aspen. Of these, the hardwoods are opportunistic and occur in other areas as well, but spruce and fir are almost entirely restricted to areas that get very, very cold - like the steep talus slope high on Umpire Mountain, seen above. Sometimes we also see spruce and fir in somewhat unexpected settings.

The picture above is an oblique, Google Earth view of a valley nestled between Umpire Mountain, Burke Mountain, and Kirby Ridge. The steepness of the terrain is exaggerated in this view. The Burke ski area is visible on the far side of Burke Mountain (center) while the spruce forest in the photo I posted earlier is on the far right of this view, on the steep slopes of Umpire Mountain. Not surprisingly, you can see lots of conifers on these tall mountains, where a lot of snow is also visible (the photo was taken in April of 2006).

You'll also notice something else here though. The conifers aren't restricted to the mountaintop. There are also a bunch of them in the valley. What gives?

Those spruce and fir trees are present in the valley bottom because of cold air drainage. Most of the time, the mountaintops are the coldest parts of Vermont. But, during a cold, still clear night, things change. Heat rapidly radiates away from the mountains, but as air cools, it sinks. Cold air is denser than warm air. Cold air from the mountains surrounding this little valley trickles down to the valley bottom, where it pools. This cold air is no joke. In fact, on a frigid night in 1933, the town of Bloomfield 18 miles to the northeast of this basin measured a low temperature of -50, tied with a more recent record in Maine for the coldest temperature ever recorded in New England. There aren't any weather stations in Victory Basin (the area described above) though, and I wouldn't be surprised if it was even colder there that night.

There aren't many trees that can stand up to -50 degree temperatures, but spruce is one of them. Together with fir and a few other species, the cold air pockets of New England and upstate New York support a natural community called Lowland Spruce-Fir Forest.

View Larger Map

The above map offers a view of Victory Basin, with the lowland spruce-fir forests and associated wetlands clearly visible (this is the same area where I saw a moose a few weeks ago). If you wander north on the above map you will notice a pattern of the darker green conifers being present both in the valleys and on the peaks. If you continue dragging the view north you will come to the Nulhegan Basin, an even larger cold-air drainage area. Both the Victory and Nulhegan basins support species similar to that in the boreal taigas in Canada, ranging from rhodora to the state endangered spruce grouse. Not surprisingly, moose are very abundant in these areas as well. Snowshoe hare and beaver are abundant, and it's possible that even lynx inhabit these icy forests.

Cold air drainage isn't limited to icy climates like Vermont's either. They play a part in the ecology and natural history of the sunny Santa Monica Mountains in Malibu, California as well. I've seen frozen ground and 'frost heaves' in this part of Malibu Creek State Park:

View Larger Map

This is just a few miles from the immediate coastline, where temperatures very rarely drop below 40F and hard freezes may only occur once or twice a century. Stephen Davis of Pepperdine University has found evidence that these cold air drainages strongly affect the vegetation in the area, and he has told me that single-digit (f) temperatures are not unheard of in these isolated areas. I believe it - one spring I lived in Park Service employee housing at nearby Rocky Oaks park, another cold air drainage area, and hard freezes were common on many clear nights well into April. I had to scrape the ice off of my car windshield in the mornings with a credit card because I didn't have an ice scraper. There were even areas of black ice on some of the nearby roads on cold nights after rainstorms.

Malibu's cold air pockets are more defined by an absence than a presence. The ubiquitous laurel sumac shrub that is found over almost all of the Santa Monica Mountains does not occur in cold air drainage areas. It is said that early farmers would only plant citrus where laurel sumac was growing, because it meant frost was very rare.

Next time you are in a small valley or hollow, look at the plants around you, because they may have an icy story to tell.

Monday, October 8, 2012

Water and Rivers on Other Worlds

An incredible discovery was made recently by the Curiosity rover on Mars, that was a bit overshadowed at the time by politics and other news. Smooth pebbles were found on an alluvial fan in Gale Crater. These pebbles are evidence of water flowing over the surface of Mars for extended periods of time.

(all photos here courtesy of NASA and JPL).

We've known for a long time that Mars has water ice on it and at one time almost certainly supported liquid water. It may have small, short-lived trickles of salty water in a few places even today. The pebbles show us something else, though. The pebbles, which appear to be scattered over a large alluvial fan, show us evidence of a river or stream on Mars that probably flowed for thousands or millions of years.

Above: more outcroppings containing water-deposited pebbles)

This doesn't mean there was continuous flow in this watercourse. Mars was likely drier than Earth even back then. The alluvial fan looks a lot like those found in very dry deserts on Earth such as Death Valley and the Atacama Desert:

In those deserts the dry washes can go years or even decades between seeing any surface flow of water. When it does come, though, the dry soils, exposed rock, and sparse vegetation mean that a thunderstorm can unleash massive flash floods. The same could have been true on Mars. We don't know of any vegetation that ever existed on Mars, so it's quite possible that the flash floods would have been even more severe than on Earth, though perhaps slower-moving due to the lower gravity. Then again, Mars could have also supported some tough, hardy life similar to that which occurs in Death Valley today. We won't ever know unless we find evidence of that life, because we can't disprove that it was there by NOT finding fossils or other evidence.

Dry washes prone to flash floods are not easy places to live, but the wash probably emptied into a lake similar to those in the Great Basin today. Perhaps it was a usually-dry lake like Amargosa Dry Lake in Death Valley or perhaps it contained significant amounts of salty water all the time, like Mono Lake in the Eastern Sierras.

Most washes in even the driest deserts also have a few spots of moisture. Upstream from the alluvial fan, in a steep gorge, often near a dry waterfall, there are places where bedrock forces the scant groundwater to the surface. On Earth, these little seeps are tiny islands of life in the desert, and often support a few weathered trees such as cottonwoods. The seeps are, of course, also vital to desert animals looking for water. Whether or not Mars ever held life, there apparently were dynamic watersheds, springs, ponds, rivers, canyons, flood plains, and other water features found all over Earth.

Water is an incredibly common compound throughout the universe, and with billions of planets (and countless moons around those planets too), there are certainly untold trillions of rivers flowing on other worlds. With all those planets it seems certain there must be other life out there too, maybe quite a bit of it.

One of the most bizarre recent findings from space is that rivers need not always contain water. On Titan, which is much, much colder than Earth but does support a thick atmosphere, there are many active rivers, but of methane, not water. Perhaps even more mind-bogglingly, the rock that these rivers erode through consists primarily of water ice!

The above air photo is from the Cassini-Huygens space probe.

A Google image search for Titan Rivers will bring up a vast number of incredible photos of river systems and lakes or oceans on Titan. Interestingly these images reveal a relatively young landscape - the rivers look to be young and very active, and few impact craters are evident. It seems that Titan in fact is covered in a very extensive network of tributaries and rivers, much like Earth. Unlike those on Mars, these are still very much active. And, they can't really be called watersheds - more accurately they are 'methanesheds'.

Conversely, there are probably very hot planets where rock flows in rivers as lava, through some other substance, and water exists only as a gas? Venus is very hot and may experience some sort of drizzle, but no evidence of 'watersheds' created by other flowing liquids.

We are surrounded by incredible wonder and diversity in our universe, but the fact remains that despite all these rivers on other worlds, we are utterly dependent on our own rivers and water for our survival. We are, of course, all on one tiny planet amidst all this wonder, and for the time being unable to leave. Even if we do, Earth will always be 'home'. We need to take care of our rivers.

(all photos here courtesy of NASA and JPL).

We've known for a long time that Mars has water ice on it and at one time almost certainly supported liquid water. It may have small, short-lived trickles of salty water in a few places even today. The pebbles show us something else, though. The pebbles, which appear to be scattered over a large alluvial fan, show us evidence of a river or stream on Mars that probably flowed for thousands or millions of years.

Above: more outcroppings containing water-deposited pebbles)

This doesn't mean there was continuous flow in this watercourse. Mars was likely drier than Earth even back then. The alluvial fan looks a lot like those found in very dry deserts on Earth such as Death Valley and the Atacama Desert:

In those deserts the dry washes can go years or even decades between seeing any surface flow of water. When it does come, though, the dry soils, exposed rock, and sparse vegetation mean that a thunderstorm can unleash massive flash floods. The same could have been true on Mars. We don't know of any vegetation that ever existed on Mars, so it's quite possible that the flash floods would have been even more severe than on Earth, though perhaps slower-moving due to the lower gravity. Then again, Mars could have also supported some tough, hardy life similar to that which occurs in Death Valley today. We won't ever know unless we find evidence of that life, because we can't disprove that it was there by NOT finding fossils or other evidence.

Dry washes prone to flash floods are not easy places to live, but the wash probably emptied into a lake similar to those in the Great Basin today. Perhaps it was a usually-dry lake like Amargosa Dry Lake in Death Valley or perhaps it contained significant amounts of salty water all the time, like Mono Lake in the Eastern Sierras.

Most washes in even the driest deserts also have a few spots of moisture. Upstream from the alluvial fan, in a steep gorge, often near a dry waterfall, there are places where bedrock forces the scant groundwater to the surface. On Earth, these little seeps are tiny islands of life in the desert, and often support a few weathered trees such as cottonwoods. The seeps are, of course, also vital to desert animals looking for water. Whether or not Mars ever held life, there apparently were dynamic watersheds, springs, ponds, rivers, canyons, flood plains, and other water features found all over Earth.

Water is an incredibly common compound throughout the universe, and with billions of planets (and countless moons around those planets too), there are certainly untold trillions of rivers flowing on other worlds. With all those planets it seems certain there must be other life out there too, maybe quite a bit of it.

One of the most bizarre recent findings from space is that rivers need not always contain water. On Titan, which is much, much colder than Earth but does support a thick atmosphere, there are many active rivers, but of methane, not water. Perhaps even more mind-bogglingly, the rock that these rivers erode through consists primarily of water ice!

The above air photo is from the Cassini-Huygens space probe.

A Google image search for Titan Rivers will bring up a vast number of incredible photos of river systems and lakes or oceans on Titan. Interestingly these images reveal a relatively young landscape - the rivers look to be young and very active, and few impact craters are evident. It seems that Titan in fact is covered in a very extensive network of tributaries and rivers, much like Earth. Unlike those on Mars, these are still very much active. And, they can't really be called watersheds - more accurately they are 'methanesheds'.

Conversely, there are probably very hot planets where rock flows in rivers as lava, through some other substance, and water exists only as a gas? Venus is very hot and may experience some sort of drizzle, but no evidence of 'watersheds' created by other flowing liquids.

We are surrounded by incredible wonder and diversity in our universe, but the fact remains that despite all these rivers on other worlds, we are utterly dependent on our own rivers and water for our survival. We are, of course, all on one tiny planet amidst all this wonder, and for the time being unable to leave. Even if we do, Earth will always be 'home'. We need to take care of our rivers.

Monday, October 1, 2012

New Iphone 5 and Gratuitous Vermont Fall Foliage

My phone recently died, giving me an excuse to upgrade to an iPhone 5. This post is ostensively a review of the new iPhone 5, but is really just an excuse to post beautiful fall foliage photos.

The iPhone 5 camera seems fairly similar to its predecessor, at least to someone who isn't an expert in photography. However, there are a few new features. First of all, photos snap a lot quicker, which is nice for taking photos of things seen from a moving vehicle.

Note: don't be a distracted driver! Have the passenger take the photos.

There's also a HDR feature - which existed in the iPhone 4 also, and allows for brighter colors and a more even exposure. It can also lead to 'fake' looking photos with exaggerated color.. But, in the case of Vermont fall foliage, the colors are always vastly more vivid than I'm able to capture in a photo, and the HDR gives a somewhat better representation of that.

This was an HDR photo - note the vivid colors but also the 'ghost' trees on the horizon.

The HDR can cause weird photo 'artifacts' when photographing fast-moving objects, because it really takes a compilation of several photos.

Perhaps the funnest new feature is the panorama feature which allows the creation of a 180 degree panorama (vertical or horizontal) without using an external app. It works great. Click on the photo below for a larger view of a foot, horse, and snowmobile bridge across the Moose River:

This bridge is at the point where the river flows out of the Victory Basin.

Looking downstream, the river is a typical beautiful Vermont river, with riffles and pools:

Looking upstream, the alder swamps and black cherry floodplain woodlands are visible in the distance:

The maples are vividly red, especially the well-named red maples, and the birch are a striking shade of yellow.

Some may disagree but I find that a drizzly, dark day like today really brings out hte fall foliage. Though, to be fair, the sun through the yellow birch leaves is also amazing. The beech trees are still green.

Oh yeah.. I almost forgot about the iPhone. In short, people who are very into the art of photography will not want to use the iPhone as their primary camera, but for people like me more interested in easily being able to take photos for outreach or science, it works great.

For more fall foliage photos click here. I'll be updating this as the season goes on.

Oh yes, one other thing... it's advisable to avoid using the iPhone 5 maps for directions in rural areas. Vermont isn't as hazardous as the desert, except in a blizzard perhaps, but if you want to explore the backroads of the Northeast Kingdom of Vermont, where the foliage is near peak right now, bring a paper map and better yet enquire locally at any store or info center. People love sharing their favorite roads and places. Even more so in the winter... iPhone maps and even Google Maps often don't 'know' that many roads are closed in the winter or require 4*4 (or a snowmobile).

Tuesday, September 25, 2012

Encountering a Bull Moose in the Wildest Corner of Vermont

I walked into the boreal woods by myself today, but I soon realized I was not alone.

He wasn't exactly making a secret of his presence. I encountered several scrapings in the wet mud - some so recent that water was still seeping into the hoof prints. He'd scraped the bark off of trees, crashed through speckled alder thickets, and left huge footprints in the sphagnum moss of a bog. The message was clear: if you were a rival, you'd better stay away... but if you were a receptive female, you were quite welcome.

I wasn't out looking for moose, but rather for wetlands - in particular bogs and spruce swamps. I've been spending a lot of time in the Victory Basin lately, a remote part of the Northeast Kingdom of Vermont, characterized by incredibly cold winter temperatures and harsh granite-derived soils. The ecosystems in this basin are similar to those hundreds of miles north in the boreal forest of Canada... and while moose occur in most of Vermont they are especially abundant in this northern cold setting.

Above: Lowland Spruce-Fir forest, a landscape often inhabited by moose.

After fighting through some dense vegetation I emerged on the shores of a large beaver pond. I began taking notes on the spruce forest when I noticed two brown 'lumps' across the pond to my south. The first was the root mass of a fallen tree, but when I glanced at the second I noticed movement. Was it a brown leaf flicking in the wind? The movement repeated, and soon the entire lump moved slightly.

With the movement I saw a head, ears, and yes, two large antlers. I made eye contact with the very moose who had marked this area as his territory (if it were a different male moose I'd be instead witnessing a fight between the two!). I'm sure he soon realized I was not a moose. We watched each other for a time. He wiggled his ears a few more times, and made a soft, repetitive grunting sound. I'm not sure if he was directing the sound towards me, or was still hoping there was also a female moose nearby.

I certainly wasn't going to walk closer to a rutting bull moose, so after we watched each other for a while I disappeared back into the thick fir forest along the pond.

Above: A moose jawbone found in a different part of Victory Basin. A moose biologist told me that this moose was perhaps two years old when it died.

He wasn't exactly making a secret of his presence. I encountered several scrapings in the wet mud - some so recent that water was still seeping into the hoof prints. He'd scraped the bark off of trees, crashed through speckled alder thickets, and left huge footprints in the sphagnum moss of a bog. The message was clear: if you were a rival, you'd better stay away... but if you were a receptive female, you were quite welcome.

I wasn't out looking for moose, but rather for wetlands - in particular bogs and spruce swamps. I've been spending a lot of time in the Victory Basin lately, a remote part of the Northeast Kingdom of Vermont, characterized by incredibly cold winter temperatures and harsh granite-derived soils. The ecosystems in this basin are similar to those hundreds of miles north in the boreal forest of Canada... and while moose occur in most of Vermont they are especially abundant in this northern cold setting.

Above: Lowland Spruce-Fir forest, a landscape often inhabited by moose.

After fighting through some dense vegetation I emerged on the shores of a large beaver pond. I began taking notes on the spruce forest when I noticed two brown 'lumps' across the pond to my south. The first was the root mass of a fallen tree, but when I glanced at the second I noticed movement. Was it a brown leaf flicking in the wind? The movement repeated, and soon the entire lump moved slightly.

With the movement I saw a head, ears, and yes, two large antlers. I made eye contact with the very moose who had marked this area as his territory (if it were a different male moose I'd be instead witnessing a fight between the two!). I'm sure he soon realized I was not a moose. We watched each other for a time. He wiggled his ears a few more times, and made a soft, repetitive grunting sound. I'm not sure if he was directing the sound towards me, or was still hoping there was also a female moose nearby.

I certainly wasn't going to walk closer to a rutting bull moose, so after we watched each other for a while I disappeared back into the thick fir forest along the pond.

Above: A moose jawbone found in a different part of Victory Basin. A moose biologist told me that this moose was perhaps two years old when it died.

Tuesday, September 18, 2012

Silver Maple: A Majestic Tree of Slow Water

Fall is coming to Vermont, and the maples are already starting to turn vivid shades of yellow, orange, and red. Among these maples is a tree that is known for its preference for slow-moving water - silver maple, or Acer saccharinum.

Above: the silver maples along Lake Champlain were already starting to turn colors in late August.

I've mentioned two other river-loving trees in this blog before - sycamores, which grows along fast-moving cobble-strewn rivers from Vermont south, and cottonwoods, which favor sandy areas like river sandbars and lakeside beaches. Silver maples are a bit different, though. They thrive in areas where water settles in during the spring, and stays there - sometimes for several months!

Above: this area of Lakeside Floodplain Forest along Lake Champlain is dry right now, but you can see a high-water line on the tree trunks. Some trees along Lake Champlain have high-water marks over 6 feet up the tree, probably from last year's record-breaking flooding.

In Vermont, Silver Maple occurs in lakeside floodplain forests along Lake Champlain as well as in riverine floodplain forests along our larger, slow-moving rivers and streams. It is especially common on natural levees. In northern Vermont, it can sometimes hybridize with red maple - which is odd, because while red maple commonly occurs in swamps, it doesn't often occur in floodplain forests.

Above: silver maples near an oxbow lake along the Clyde River.

Silver maple can survive being inundated for several months each year. It is actually a bit similar to baldcypress in its habitat and ecological niche, though these trees are not related (baldcypress also can't survive in Vermont - it's way too cold). The best way to find silver maple is by looking in a floodplain near a large river, but it can also be identified by it's very deeply divided leaves and its shaggy bark.

Silver maple is native to a large chunk of the eastern United States as well as some of southeastern Canada.

The above picture is from the US Forest Service silvics manual.

Perhaps the most important value of silver maple is in its ability to reduce erosion and filter water during floods. Sadly, as many floodplains have been developed or river flood cycles altered, large stands of silver maple are not as common as they once were. It is also widely planted as a landscape tree. Silver maple timber isn't especially valuable, probably in part because of the contorted form of these trees. Likewise, the tree can be used to produce syrup, but it reportedly doesn't taste as good as sugar maple syrup, so there isn't much reason to bother with it. Its natural habitat is often iced over or flooded during sugaring season anyway. Squirrels and beavers eat portions of the tree and ducks and other birds nest in its branches. The shade it provides to waterways is beneficial to cold-water fish such as trout. It is also valued for the other plants it grows in association with - in particular ostrich fern, which produces the delicious fiddleheads that are often eaten in New England.

Above: Silver maple seedlings sprout the year after severe lake flooding in Lake Champlain. As these trees grow, beavers will cut down some of them to eat the bark, and squirrels will eat their spring buds. In time a few of them will replace the larger silver maple trees towering over them and continue the life of this forest.

So, if you're out enjoying the fall foliage this year in New England, stop by a river and enjoy the silver maple - it isn't as vibrant as red maple in the fall, but still quite beautiful, and the ferns under the trees also turn pleasant rusty brown this time of year. Just about any large river in New England will have some silver maples on its banks, but if you're in Vermont, Ethan Allen Homestead in Burlington has a very accessible silver maple forest just a few miles from downtown. Or you can check out where I've observed silver maple trees on iNaturalist (note that only the 'pointy' markers on that map have exact location).

View Larger Map

Above: a small patch of silver maple in a Wildlife Management Area in Addison County that is also open to the public. There is also a boat launch here, so you could explore the flooded forest by canoe or kayak in the spring. The area is popular for fishing and duck hunting, and both ducks and fish also benefit from these trees.

Above: the silver maples along Lake Champlain were already starting to turn colors in late August.

I've mentioned two other river-loving trees in this blog before - sycamores, which grows along fast-moving cobble-strewn rivers from Vermont south, and cottonwoods, which favor sandy areas like river sandbars and lakeside beaches. Silver maples are a bit different, though. They thrive in areas where water settles in during the spring, and stays there - sometimes for several months!

Above: this area of Lakeside Floodplain Forest along Lake Champlain is dry right now, but you can see a high-water line on the tree trunks. Some trees along Lake Champlain have high-water marks over 6 feet up the tree, probably from last year's record-breaking flooding.

In Vermont, Silver Maple occurs in lakeside floodplain forests along Lake Champlain as well as in riverine floodplain forests along our larger, slow-moving rivers and streams. It is especially common on natural levees. In northern Vermont, it can sometimes hybridize with red maple - which is odd, because while red maple commonly occurs in swamps, it doesn't often occur in floodplain forests.

Above: silver maples near an oxbow lake along the Clyde River.

Silver maple can survive being inundated for several months each year. It is actually a bit similar to baldcypress in its habitat and ecological niche, though these trees are not related (baldcypress also can't survive in Vermont - it's way too cold). The best way to find silver maple is by looking in a floodplain near a large river, but it can also be identified by it's very deeply divided leaves and its shaggy bark.

Silver maple is native to a large chunk of the eastern United States as well as some of southeastern Canada.

The above picture is from the US Forest Service silvics manual.

Perhaps the most important value of silver maple is in its ability to reduce erosion and filter water during floods. Sadly, as many floodplains have been developed or river flood cycles altered, large stands of silver maple are not as common as they once were. It is also widely planted as a landscape tree. Silver maple timber isn't especially valuable, probably in part because of the contorted form of these trees. Likewise, the tree can be used to produce syrup, but it reportedly doesn't taste as good as sugar maple syrup, so there isn't much reason to bother with it. Its natural habitat is often iced over or flooded during sugaring season anyway. Squirrels and beavers eat portions of the tree and ducks and other birds nest in its branches. The shade it provides to waterways is beneficial to cold-water fish such as trout. It is also valued for the other plants it grows in association with - in particular ostrich fern, which produces the delicious fiddleheads that are often eaten in New England.

Above: Silver maple seedlings sprout the year after severe lake flooding in Lake Champlain. As these trees grow, beavers will cut down some of them to eat the bark, and squirrels will eat their spring buds. In time a few of them will replace the larger silver maple trees towering over them and continue the life of this forest.

So, if you're out enjoying the fall foliage this year in New England, stop by a river and enjoy the silver maple - it isn't as vibrant as red maple in the fall, but still quite beautiful, and the ferns under the trees also turn pleasant rusty brown this time of year. Just about any large river in New England will have some silver maples on its banks, but if you're in Vermont, Ethan Allen Homestead in Burlington has a very accessible silver maple forest just a few miles from downtown. Or you can check out where I've observed silver maple trees on iNaturalist (note that only the 'pointy' markers on that map have exact location).

View Larger Map

Above: a small patch of silver maple in a Wildlife Management Area in Addison County that is also open to the public. There is also a boat launch here, so you could explore the flooded forest by canoe or kayak in the spring. The area is popular for fishing and duck hunting, and both ducks and fish also benefit from these trees.

Monday, September 10, 2012

What Does This Winter Hold?

This Saturday another round of severe storms blasted through Vermont, but unlike previous severe thunderstorms of this year it brought something with it: cold air. Yesterday was a cool day and today even cooler - Montpelier never got out of the 50s today, and an early fall chill is in the air tonight. Some of the coldest parts of Vermont will probably even get a mild frost tonight.

Winter is still several months away, but with trees starting to turn color, squirrels hoarding acorns, and geese starting to act restless, people are starting to talk about what the next winter might hold. A week or so ago my girlfriend was at a farm in a cold part of rural Vermont and a local resident pointed out a woolly bear caterpillar and noted that the abundance of brown fuzz on the caterpillar might mean that a cold winter was on the way.

I've heard elsewhere, though that more brown fuzz indicates a milder winter, or that more fluffy fuzz means more snow. I'm more inclined to trust the local knowledge, but at the same time, the caterpillars aren't sending a clear message, at least not one I know how to read.

The maple trees are sending a less ambiguous message. Regardless of whether it is warmer, colder, snowier, or drier than average, colder weather is on the way, and soon. Even a slightly warmer than average Vermont winter can see significant periods of subzero weather.

But what are other people saying? Well, the Farmer's Almanac predicts 'cold and snowy' for northern New England, but most Vermont winters are 'cold and snowy' by overall US standards, so I'm not sure if they are calling for an especially snowy year, or just the normal cold weather we get every year. The Accu-Weather forecast does not mention anything in Vermont at all, which I suppose is a forecast for a normal winter, but does mention later in the forecast that weak to moderate El Ninos like we may be having tend to bring snowy weather to New England.

Last year, both the Accu-Weather and Farmer's Almanac called for a very cold and snowy winter in Vermont. As anyone here will tell you, it was an extraordinarily snowless and mild winter compared to normal. (though the Accu-Weather forecast for 2010-2011 called for heavy snow and indeed it was the second snowiest year on record in much of Vermont. I suppose the Accu-Weather forecast is a bit like a broken clock that is right every time it snows a lot.)

NOAA made a rather vague forecast last year - somewhat above average precipitation, and an equal chance of warm, cold, or average weather. The precipitation was below average and the temperature above average. This year the current forecast as of early September (they are updated fairly often) calls for above average temperatures and has no precipitation trend forecast in Vermont (but perhaps stormier than average conditions along the New England coast). Note that this forecast simply says that there is a 40% chance of above average temperatures, and a lower chance of colder than average or normal temperatures. This is averaged over the entire time period, and doesn't mean some periods couldn't be very cold. And of course, the forecast could just be wrong, like they all were last year.

Above: NOAA temperature forecast for December 2012-February 2013. See the link above for more maps.

I'm not going to make a winter forecast for Vermont this year, because I don't think there are any strong signals one way or another. I will note that overall monthly temperatures have been above average for a very long time - I think over a year - so unless there is a significant pattern change we can guess that it may be a bit warmer than average. In addition to current jet stream patterns the climate of the whole globe is warmer than in the recent past, causing an increased likelihood of warmer temperatures overall. BUT, somewhat paradoxically, the warming has melted much of the sea ice in the Arctic, and there are indications that the lack of Arctic ice can move the jet stream and actually lead to blizzards and Arctic blasts over places like Vermont. Similar phenomena were documented in several Northern Hemisphere areas over the past few years, including last year (just not in the continental US that time). So... it's possible our string of warm conditions will be interrupted by a harsh arctic blast of the kind we haven't seen in many years.

So all I can say for sure is it should be interesting. I will say that I have seen indications that the Vermont oaks are possibly 'concerned' about a future weather event, though it may be that the indicator I use to monitor this (which seems to correlate with California drought) may just have been triggered by the dry summer. We'll see!

For those of you in California, the climate indicators are much more strong this year. We're probably heading into a weak to moderate El Nino, and as many people already know, El Nino tends to correlate with above average, sometimes torrential rain in southern and central California. Not all El Nino years are wet, but averaged over all the El Nino years we have records for, the average precipitation in California is much higher than non-El-Nino years. Hopefully California will see some drought relief, and perhaps Texas and Florida as well.

Wednesday, September 5, 2012

Isaac's Remnants Selectively Soak Northern Vermont

Northern Vermont had a somewhat surprising soaking last night.

If the weather forecasts for a few days ago, the headline for this post could have been Isaac's Remnants Selectively Soak Southern Vermont... which would have sounded better, with alliteration and all. That isn't what happened, though. The low pressure area containing copious moisture from the remnants of Hurricane Isaac made a last minute jog to the north. Anyone north of a line from Virgennes to Saint Johnsbury got soaked, while those to the south of that line experienced a run of the mill late summer storm. The Adirondacks got a drenching as well, and apparently also southern Quebec, though I don't have precipitation figures from there.

Burlington picked up more than 3 inches of rain last night, the most it's seen out of one storm since Irene came through last year. Some of the northernmost parts of Vermont picked up more than six inches of rain! Here in Montpelier we were right on the edge of the heavy rain, and we picked up between an inch and 1.5 inches of rain overnight.

Above: Estimated and reported precipitation amounts courtesy of NOAA. Unfortunately the map is a bit jumbled but you can pick up the trends...

The North Branch of the Winooski has risen, though not dramatically so, because it has been so dry. Further north, where heavier rain fell, river raises were more dramatic with the Missisquoi River raising almost EIGHT FEET overnight! It actually rose a bit over flood stage in Troy. I haven't heard of it doing any damage, but it's certainly an unexpected event in this otherwise dry summer.

For most of Vermont, and indeed most of the areas affected by Isaac, the rain was welcome despite the problems it caused.

Meanwhile, way out in the Atlantic, Leslie has fought off wind shear and has become a hurricane. Leslie isn't going to hit New England as was previously considered a slight possibility, but is likely to seriously impact far eastern Canada. By traveling north and strengthening, it will slow down a front passing over Vermont this weekend, perhaps contributing to another storm somewhat similar to the one we just had. Since most areas picked up heavy rain this time, we need to watch out for possible flooding this weekend. Fall is building in, and it's certainly a change from the dry summer we've been having.

Incidentally, it isn't only the eastern half of the United States being impacted by moisture from dissipated hurricanes. Scattered showers from a tropical remnant are also affecting much of California. Rainfall totals have been very light, but this is still the dry season, so any precipitation is unusual. There is also the chance of dry lightning that could cause fires.

As fall builds in, people have begun talking about winter, especially here in Vermont where winters can be so dramatic. I'll have a post about some of the winter forecasts being thrown around, soon.

If the weather forecasts for a few days ago, the headline for this post could have been Isaac's Remnants Selectively Soak Southern Vermont... which would have sounded better, with alliteration and all. That isn't what happened, though. The low pressure area containing copious moisture from the remnants of Hurricane Isaac made a last minute jog to the north. Anyone north of a line from Virgennes to Saint Johnsbury got soaked, while those to the south of that line experienced a run of the mill late summer storm. The Adirondacks got a drenching as well, and apparently also southern Quebec, though I don't have precipitation figures from there.

Burlington picked up more than 3 inches of rain last night, the most it's seen out of one storm since Irene came through last year. Some of the northernmost parts of Vermont picked up more than six inches of rain! Here in Montpelier we were right on the edge of the heavy rain, and we picked up between an inch and 1.5 inches of rain overnight.

Above: Estimated and reported precipitation amounts courtesy of NOAA. Unfortunately the map is a bit jumbled but you can pick up the trends...

The North Branch of the Winooski has risen, though not dramatically so, because it has been so dry. Further north, where heavier rain fell, river raises were more dramatic with the Missisquoi River raising almost EIGHT FEET overnight! It actually rose a bit over flood stage in Troy. I haven't heard of it doing any damage, but it's certainly an unexpected event in this otherwise dry summer.

For most of Vermont, and indeed most of the areas affected by Isaac, the rain was welcome despite the problems it caused.

Meanwhile, way out in the Atlantic, Leslie has fought off wind shear and has become a hurricane. Leslie isn't going to hit New England as was previously considered a slight possibility, but is likely to seriously impact far eastern Canada. By traveling north and strengthening, it will slow down a front passing over Vermont this weekend, perhaps contributing to another storm somewhat similar to the one we just had. Since most areas picked up heavy rain this time, we need to watch out for possible flooding this weekend. Fall is building in, and it's certainly a change from the dry summer we've been having.

Incidentally, it isn't only the eastern half of the United States being impacted by moisture from dissipated hurricanes. Scattered showers from a tropical remnant are also affecting much of California. Rainfall totals have been very light, but this is still the dry season, so any precipitation is unusual. There is also the chance of dry lightning that could cause fires.

As fall builds in, people have begun talking about winter, especially here in Vermont where winters can be so dramatic. I'll have a post about some of the winter forecasts being thrown around, soon.

Saturday, September 1, 2012

Hurricane Isaac: An Ill Wind that Blows some Good

Hurricane Isaac just slammed the New Orleans area, causing a great deal of flooding to Plaquemines Parish to its south. It also killed quite a few people in Haiti. While it never got beyond Category 1, it was a very large, wet, and slow-miving storm, and dropped as much as 20 inches of rain in New Orleans! (in comparison, the disastrous rains of Irene in Vermont last year were mostly under 10 inches).

A wet storm wasn't welcome in New Orleans, but it sure was to the north as it moved up the Mississippi River Valley. That area is experiencing very severe drought, and the deluge that just passed through the area helped reduce the drought quite a bit. Unfortunately, it was too late for many farmers.

Above: NOAA map of drought conditions.

Jeff Masters' blog has a lot of great info about this hurricane and its positive and negative effects. The expression "it's an ill wind that blows no good" seems to apply here. Many natural disasters have upsides to some, even as they harm others. Irene pulled Vermont together in a tremendous way, though I would definitely say Irene blew much more ill than good for Vermont. Isaac, on the other hand, may actually be remembered as much for its benefits as its harm, at least in the US. (Haiti, on the other hand, has horrific flooding in almost any storm, because its extreme poverty has caused people to remove all of the trees from their slopes, resulting in extreme watershed degradation. The deaths in Haiti are tragic but seem more related to social and environmental factors than the severity of Isaac per se). Isaac will even probably kick some moisture into a front crossing Vermont early next week. We could certainly use the rain here, though we haven't had as severe drought as most of the US.

Tropical systems may cause a lot of devastation, but they are part of our climate and if they were to stop happening (which is admittedly not going to happen), precipitation would be greatly decreased in some areas. Here's a very neat map of the highest recorded precipitation dropped on each state by tropical system, again from NOAA:

Hawaii wasn't included but of course is affected by tropical systems, heavily at times. Alaska has never been hit by a tropical system... moisture from their remnants has affected Alaska, but by then it has often merged with other storm systems so it's hard to say how much the hurricane or typhoon caused. Here's a very neat Wikipidia page with detailed numbers. It appears Floyd beat out Irene in terms of highest precipitation, though it caused less damage, probably because last summer was so wet even before Irene hit. It's incredible that the entire US is affected by tropical storm and hurricane precipitation, including Wyoming (!) and Washington State. If you dig into old records, you will also learn that southern California is vulnerable to rare tropical systems - notable not only due to their ability to cause severe flooding but that they usually occur at the end of the dry season, when coastal California usually receives little to no precipitation for months at a time (a complete lack of rainfall from June through September is common and heavy summer rain is nearly unheard of)

Speaking of ill winds, it's worth keeping an eye on Tropical Storm Leslie. It may be far from land, but some computer models have showed it possibly impacting the east coast of US or Canada. It's far too far away to be concerned about yet, especially since many computer models show it dissipating harmlessly at sea. But, it's good to be prepared.

On a side note, I have to apologize for the lack of photos in my blog. My iPhone died, and I won't have a new phone for a few weeks as I've opted to try out the new iPhone 5 rather than buying an older one. We'll see how that goes!

A wet storm wasn't welcome in New Orleans, but it sure was to the north as it moved up the Mississippi River Valley. That area is experiencing very severe drought, and the deluge that just passed through the area helped reduce the drought quite a bit. Unfortunately, it was too late for many farmers.

Above: NOAA map of drought conditions.

Jeff Masters' blog has a lot of great info about this hurricane and its positive and negative effects. The expression "it's an ill wind that blows no good" seems to apply here. Many natural disasters have upsides to some, even as they harm others. Irene pulled Vermont together in a tremendous way, though I would definitely say Irene blew much more ill than good for Vermont. Isaac, on the other hand, may actually be remembered as much for its benefits as its harm, at least in the US. (Haiti, on the other hand, has horrific flooding in almost any storm, because its extreme poverty has caused people to remove all of the trees from their slopes, resulting in extreme watershed degradation. The deaths in Haiti are tragic but seem more related to social and environmental factors than the severity of Isaac per se). Isaac will even probably kick some moisture into a front crossing Vermont early next week. We could certainly use the rain here, though we haven't had as severe drought as most of the US.

Tropical systems may cause a lot of devastation, but they are part of our climate and if they were to stop happening (which is admittedly not going to happen), precipitation would be greatly decreased in some areas. Here's a very neat map of the highest recorded precipitation dropped on each state by tropical system, again from NOAA:

Hawaii wasn't included but of course is affected by tropical systems, heavily at times. Alaska has never been hit by a tropical system... moisture from their remnants has affected Alaska, but by then it has often merged with other storm systems so it's hard to say how much the hurricane or typhoon caused. Here's a very neat Wikipidia page with detailed numbers. It appears Floyd beat out Irene in terms of highest precipitation, though it caused less damage, probably because last summer was so wet even before Irene hit. It's incredible that the entire US is affected by tropical storm and hurricane precipitation, including Wyoming (!) and Washington State. If you dig into old records, you will also learn that southern California is vulnerable to rare tropical systems - notable not only due to their ability to cause severe flooding but that they usually occur at the end of the dry season, when coastal California usually receives little to no precipitation for months at a time (a complete lack of rainfall from June through September is common and heavy summer rain is nearly unheard of)

Speaking of ill winds, it's worth keeping an eye on Tropical Storm Leslie. It may be far from land, but some computer models have showed it possibly impacting the east coast of US or Canada. It's far too far away to be concerned about yet, especially since many computer models show it dissipating harmlessly at sea. But, it's good to be prepared.

On a side note, I have to apologize for the lack of photos in my blog. My iPhone died, and I won't have a new phone for a few weeks as I've opted to try out the new iPhone 5 rather than buying an older one. We'll see how that goes!

Monday, August 27, 2012

Vermont Looks Back on Irene a Year Later

Last weekend we traveled to southern Vermont to attend a good friend's wedding. Through our travels we came across meandering, slow trickles of water within vast, scoured channels. We were seeing the results of Irene, a year after the fact.

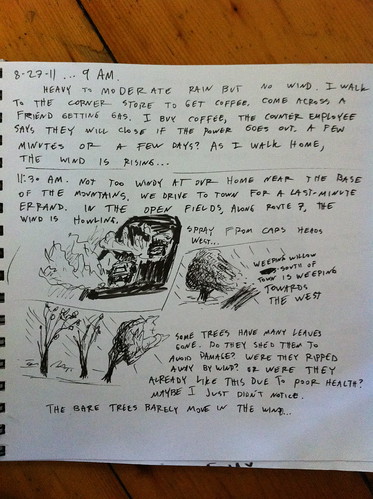

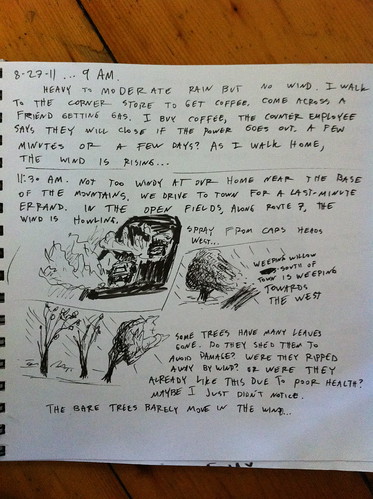

Exactly a year ago today, we were at a different wedding (weddings and hurricanes seem to share peak seasons) and planning to leave early so we could get home before Irene hit Vermont. Like many people, I'd already been following the storm for several days, and knew it could be bad. No one really knew just how bad it would be... though a few computer models that most disbelieved ended up predicting the storm fairly accurately several days in advance:

Above, the GFS computer model predicts torrential rains in Vermont, four days in advance.

My friends and anyone else who was reading this blog a year ago will remember that we were evacuated from East Middlebury, where severe flooding took place. I'd been taking notes about the storm while it happened, but they end abruptly when we were told we had to leave.

Above: flood debris left in the Middlebury River by Irene.

East Middlebury was mostly spared, but other towns were not as lucky. As everyone now knows, the damage was catastrophic in many places. Many homes were destroyed and many more were trapped in their rural homes for many days. Thankfully, Vermont is sparsely populated and people are usually prepared for holing up for a few days, often during blizzards. The peak of the floods happened during the afternoon on a Sunday, so few were on the roads and people didn't have their homes collapse while they slept. The death toll was very low.