We awoke this morning to the sound of raindrops and gusty winds. Just the sort of weather you'd expect in late October. No hurricane winds, just enough wind to blow the rain against the window.

As I look online and hear from friends, it looks like Vermont was mostly spared Sandy's damage. There are a few trees down and a few power outages. But hear in Montpelier, if I didn't know what was happening elsewhere, the only thing odd I would have noticed was the odd clouds and the much warmer rain than usual. Yesterday was actually a somewhat nice day.

My heart goes out to those in the Midatlantic and other areas that were affected by this storm. There will be much, much more to say about Sandy in the future, but for now, I'm just thankful we were spared this time. After what happened in Irene we would not have done well with another disaster.

Matt Sutkoski of the Weather Rapport blog (from the Burlington Free Press) has pointed out that the White Mountains may have also shielded us from much of the rain and wind. Mount Washington picked up a 140 mph wind gust! The complex topography of Vermont makes rain and especially wind hard to predict. During Irene, East Middlebury had almost no wind and the rain, while heavy, was not catastrophic. Little did we know the rdige behind our home had picked up around 10 inches of rain in less than 24 hours... at least we didn't know until the river came through town.

Best of luck out there.

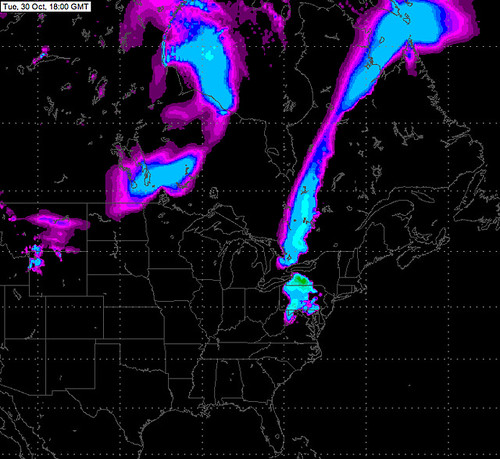

Tuesday, October 30, 2012

Sunday, October 28, 2012

Hurricane Sandy Bears Down on East Coast

It feels good to be home in Vermont.

This weekend we were in New York City for a wedding. It was great to attend the wedding and see frields, but being in one of the world's largest cities while it awaited a massive storm was an odd experience.

People were going about their business yesterday, but they were talking. Some said it would be no big deal. Others were worried. No one really knew, of course. Sandy is following a track different from other storms that we know of, so even the experts watching the storm aren't sure what is to come. Online, people argued and bickered as they often do, with some dismissing the storm as insignificant, and others making ridiculous doomsday predictions. Some people even posted comments about this being the biggest storm that 'ever existed' - very unlikely considering the multi-billion year history of our planet's atmosphere. It's not the biggest storm ever.. but it is a big, weird, scary storm.

Last night I didn't get much sleep, for a variety of reasons. I laid and listened on an air mattress to the whistling of a breeze outside the window while sirens wailed. In most parts of Vermont you don't hear all that many sirens, though they were common in California where I grew up. I wondered if these New York sirens were related to drunken halloween party revelers... or to an early arrival of Sandy. As I drifted in and out of sleep, I wondered if the storm had come early and we would be trapped in NYC for the next few days. I wondered what the hurricane-force winds would look and sound like as they raged through the manmade canyons of Manhattan. Amidst fitful dreams I realized that if the subways filled with water, millions of rats would be forced to the surface during the storm.

It's a strange and hollow feeling being so far from home in the face of something so immense and unpredictable. During Irene we had to leave our home, and I spent a sleepless night wondering if we would find it gone in the morning. Before Sandy I had a sleepless night wondering how I would GET home.

Thankfully, the morning dawned cool and breezy and overcast, but with no hurricane. (There was really no way the storm could have gotten there so fast, but such things are hard to realize when half asleep). The subways were still running at that time (as of now they are closed.) We were able to catch our bus home, and moving north we outpaced the spreading, torn low clouds.

It's difficult to say what awaits New York City and the other big coastal cities, but confidence is building that a possibly historic storm surge will occur, and that the disruptions will be massive. This won't be like Katrina - New York City is not below sea level, for one thing, and the evacuation areas are narrow and can be walked out of. But the economic impacts of this storm will be large, and unfortunately it is likely that some people will lose their lives due to not taking the storm seriously or just to bad luck.

The wind is expected to be lighter here, but not by much - wind gusts above 60 miles per hour are not out of the question in Montpelier tomorrow night, with the peaks seeing gusts well over 80 mph. The wind will be a bit lighter in Burlington, but still significant. East Middlebury and other towns just west of the Green Mountains may experience locally stronger downsloping winds - perhaps over 70 mph.

This evening the clouds looked like a sheet blowing in a strong wind...

We've got quite a storm to get through here, but I do feel safer being at home. I'd better get some sleep tonight though. Tomorrow night the windows will be rattling, tree branches will be snapping... it will be another night of restless dreams and little sleep.

This weekend we were in New York City for a wedding. It was great to attend the wedding and see frields, but being in one of the world's largest cities while it awaited a massive storm was an odd experience.

People were going about their business yesterday, but they were talking. Some said it would be no big deal. Others were worried. No one really knew, of course. Sandy is following a track different from other storms that we know of, so even the experts watching the storm aren't sure what is to come. Online, people argued and bickered as they often do, with some dismissing the storm as insignificant, and others making ridiculous doomsday predictions. Some people even posted comments about this being the biggest storm that 'ever existed' - very unlikely considering the multi-billion year history of our planet's atmosphere. It's not the biggest storm ever.. but it is a big, weird, scary storm.

Last night I didn't get much sleep, for a variety of reasons. I laid and listened on an air mattress to the whistling of a breeze outside the window while sirens wailed. In most parts of Vermont you don't hear all that many sirens, though they were common in California where I grew up. I wondered if these New York sirens were related to drunken halloween party revelers... or to an early arrival of Sandy. As I drifted in and out of sleep, I wondered if the storm had come early and we would be trapped in NYC for the next few days. I wondered what the hurricane-force winds would look and sound like as they raged through the manmade canyons of Manhattan. Amidst fitful dreams I realized that if the subways filled with water, millions of rats would be forced to the surface during the storm.

It's a strange and hollow feeling being so far from home in the face of something so immense and unpredictable. During Irene we had to leave our home, and I spent a sleepless night wondering if we would find it gone in the morning. Before Sandy I had a sleepless night wondering how I would GET home.

Thankfully, the morning dawned cool and breezy and overcast, but with no hurricane. (There was really no way the storm could have gotten there so fast, but such things are hard to realize when half asleep). The subways were still running at that time (as of now they are closed.) We were able to catch our bus home, and moving north we outpaced the spreading, torn low clouds.

It's difficult to say what awaits New York City and the other big coastal cities, but confidence is building that a possibly historic storm surge will occur, and that the disruptions will be massive. This won't be like Katrina - New York City is not below sea level, for one thing, and the evacuation areas are narrow and can be walked out of. But the economic impacts of this storm will be large, and unfortunately it is likely that some people will lose their lives due to not taking the storm seriously or just to bad luck.

The wind is expected to be lighter here, but not by much - wind gusts above 60 miles per hour are not out of the question in Montpelier tomorrow night, with the peaks seeing gusts well over 80 mph. The wind will be a bit lighter in Burlington, but still significant. East Middlebury and other towns just west of the Green Mountains may experience locally stronger downsloping winds - perhaps over 70 mph.

This evening the clouds looked like a sheet blowing in a strong wind...

We've got quite a storm to get through here, but I do feel safer being at home. I'd better get some sleep tonight though. Tomorrow night the windows will be rattling, tree branches will be snapping... it will be another night of restless dreams and little sleep.

Tuesday, October 23, 2012

A Tale of Two Models: Will A Major Storm Slam the East Coast Next Week?

Early next week in Vermont we may be experiencing a flooding downpour and raging winds. We may be experiencing fair skies, or some light drizzle. We could even be slammed by a major blizzard. Right now there is significant potential for a major storm to impact the US Northeast and far eastern Canada... but there's also a good chance we'll have rather bland weather.

Why the uncertainty? Well, as is often the case, the computer models we use to forecast the weather don't agree on what will happen.

Tropical Storm Sandy has formed way south in the Caribbean, and is moving north. It will probably strengthen into a hurricane and cause damage in Cuba, Haiti, and the Bahamas, before continuing north. After this point...

The two main weather models that offer forecasts 8 days out are the ECMWF, or Euro, and the GFS.

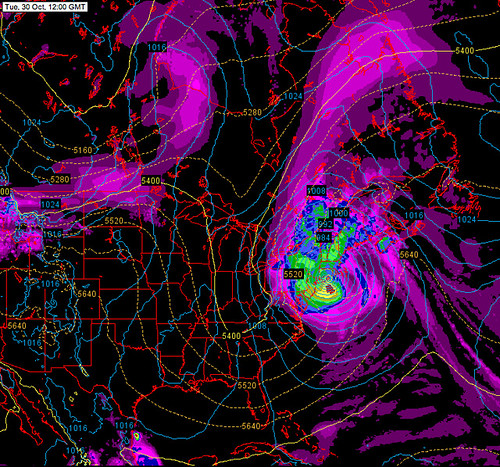

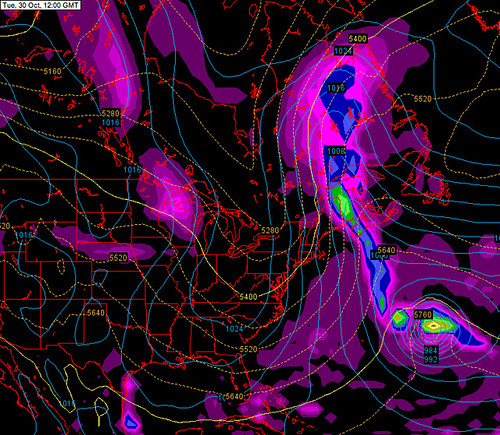

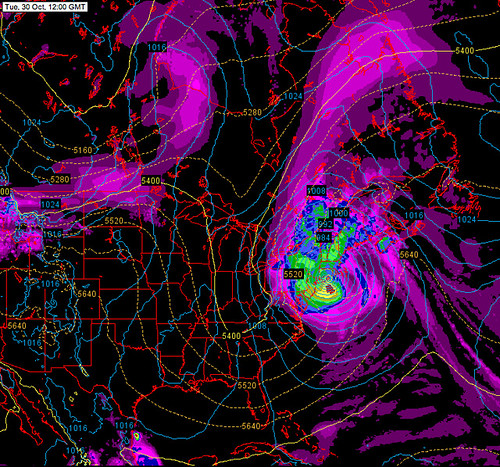

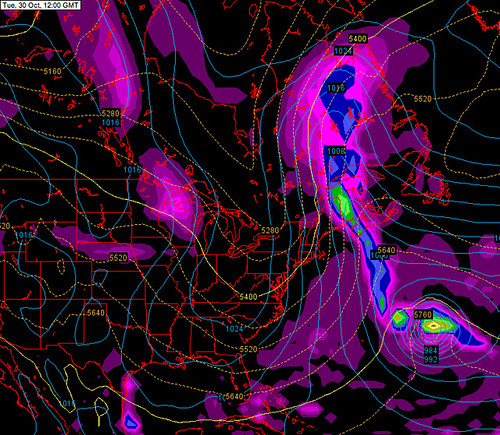

Here's what the Euro forecasts for next Tuesday (from Wunderground):

Yikes! It actually looks a bit like a colder Irene. Though, it's important to note that it would be converting to an extratropical storm. It wouldn't still be a hurricane. This might mean a less rainy and windy storm, but also means:

Yep. That's snow. If this were exactly correct Baltimore could pick up some snow, and Buffalo would be buried. It won't be exactly right though, no matter what, because this is seven days away. If there is any snow, it could occur just about anywhere in the Northeast, but won't occur everywhere.

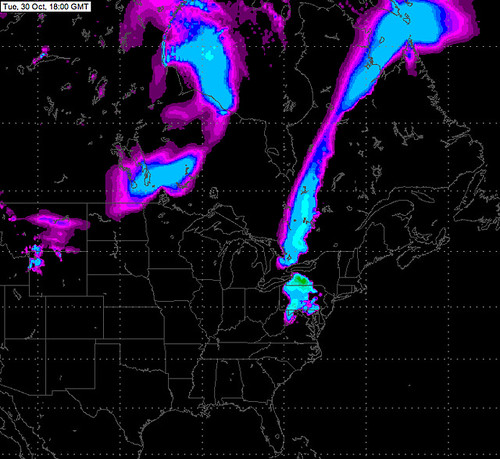

OK, so the Euro model forecasts a big storm. What does the GFS indicate?

No Nor'easter there. Northern Vermont might get some flurries, and northeastern Maine some heavy rain... but nothing extreme. Instead of forming into a nor'easter, Sandy would wander off to sea.

So which model, if any, will be correct? It's far too early to say. I think the Euro has been a bit more accurate than the GFS lately. Then again, the GFS pretty much nailed Irene's Vermont impacts over 100 hours before it happened. There's also a GFS 'ensemble' that runs a model several times with slightly varying starting conditions. About half of the ensemble members had the storm making landfall somewhere in the northeastern US, the other half had it going off to sea.

So either option is probably equally likely. If the storm does hit, the areas east of the low center would likely have the heaviest rain and strongest wind, while areas to the west would have the highest chance of picking up heavy snow. It's far too early to speculate where each could occur with any accuracy.

So... it's definitely not worth worrying about, but it's worth checking to make sure you have extra supplies and are prepared to weather a serious fall storm. This storm may miss, but it's nearly certain that a significant nor'easter will come up the coast at least once or twice this fall or winter, so it would be good to be prepared.

A hurricane combining with or turning into a nor'easter sounds a bit like science fiction, but it's happened in the past. Not surprisingly, it can result in a very serious storm that combines the wind and moisture of a hurricane with the vast size and wintry potential of a nor'easter. In 1804, the Snow Hurricane occurred when a hurricane converted to an extratropical storm and pulled in cold air on its northern and western sides, resulting in extremely heavy snow over most of New England in mid October. The Perfect Storm of 1991 was a hybrid between a hurricane and a nor'easter that formed when a nor'easter absorbed Hurricane Grace and then followed an unusual wandering path over the Gulf Stream. Incredibly, it actually formed a small new hurricane at its core, and became a monster storm that caused damage and loss of life along the US and Canadian East Coasts. Later it was remembered in the well-known movie describing the loss of a fishing boat that was unable to weather this storm.

Regardless of what happens next week, both the results of these computer models and a look back at these two intense winter storms remind us of the intensity and scope of storms that sometimes strike the eastern portion of North America.

Why the uncertainty? Well, as is often the case, the computer models we use to forecast the weather don't agree on what will happen.

Tropical Storm Sandy has formed way south in the Caribbean, and is moving north. It will probably strengthen into a hurricane and cause damage in Cuba, Haiti, and the Bahamas, before continuing north. After this point...

The two main weather models that offer forecasts 8 days out are the ECMWF, or Euro, and the GFS.

Here's what the Euro forecasts for next Tuesday (from Wunderground):

Yikes! It actually looks a bit like a colder Irene. Though, it's important to note that it would be converting to an extratropical storm. It wouldn't still be a hurricane. This might mean a less rainy and windy storm, but also means:

Yep. That's snow. If this were exactly correct Baltimore could pick up some snow, and Buffalo would be buried. It won't be exactly right though, no matter what, because this is seven days away. If there is any snow, it could occur just about anywhere in the Northeast, but won't occur everywhere.

OK, so the Euro model forecasts a big storm. What does the GFS indicate?

No Nor'easter there. Northern Vermont might get some flurries, and northeastern Maine some heavy rain... but nothing extreme. Instead of forming into a nor'easter, Sandy would wander off to sea.

So which model, if any, will be correct? It's far too early to say. I think the Euro has been a bit more accurate than the GFS lately. Then again, the GFS pretty much nailed Irene's Vermont impacts over 100 hours before it happened. There's also a GFS 'ensemble' that runs a model several times with slightly varying starting conditions. About half of the ensemble members had the storm making landfall somewhere in the northeastern US, the other half had it going off to sea.

So either option is probably equally likely. If the storm does hit, the areas east of the low center would likely have the heaviest rain and strongest wind, while areas to the west would have the highest chance of picking up heavy snow. It's far too early to speculate where each could occur with any accuracy.

So... it's definitely not worth worrying about, but it's worth checking to make sure you have extra supplies and are prepared to weather a serious fall storm. This storm may miss, but it's nearly certain that a significant nor'easter will come up the coast at least once or twice this fall or winter, so it would be good to be prepared.

A hurricane combining with or turning into a nor'easter sounds a bit like science fiction, but it's happened in the past. Not surprisingly, it can result in a very serious storm that combines the wind and moisture of a hurricane with the vast size and wintry potential of a nor'easter. In 1804, the Snow Hurricane occurred when a hurricane converted to an extratropical storm and pulled in cold air on its northern and western sides, resulting in extremely heavy snow over most of New England in mid October. The Perfect Storm of 1991 was a hybrid between a hurricane and a nor'easter that formed when a nor'easter absorbed Hurricane Grace and then followed an unusual wandering path over the Gulf Stream. Incredibly, it actually formed a small new hurricane at its core, and became a monster storm that caused damage and loss of life along the US and Canadian East Coasts. Later it was remembered in the well-known movie describing the loss of a fishing boat that was unable to weather this storm.

Regardless of what happens next week, both the results of these computer models and a look back at these two intense winter storms remind us of the intensity and scope of storms that sometimes strike the eastern portion of North America.

Tuesday, October 16, 2012

Cold Air that Flows like Water

As autumn deepens and moves towards winter, cold nights are becoming more common. We've already had one very hard freeze (last Friday night) when most areas of Vermont saw lows in the mid 20s or even colder. Aside from that, we've seen quite a few marginal frosty nights. Some areas have seen several hard freezes starting as early as mid September, while others, just like here in Montpelier, saw the growing season extend until last Friday when it abruptly ended.

Above: on October 9th, a heavy frost settled over most of the Northeast Kingdom, but not Montpelier, Plainfield, or Barre. These little plants are bedstraw (Galium).

The early season frosts seem a bit random, but they are anything but. We can't "see" temperature changes, although we can notice where frost occurs on marginal freeze nights. There's another way to see the patterns of cold air too - and it is by observing where plants occur on the landscape.

above: red spruce on a talus slope.

Most people have noticed that conifers, like pine and spruce, often occur on cold mountaintops. In Vermont, the most cold-tolerant trees are spruce, fir, paper and yellow birch, and aspen. Of these, the hardwoods are opportunistic and occur in other areas as well, but spruce and fir are almost entirely restricted to areas that get very, very cold - like the steep talus slope high on Umpire Mountain, seen above. Sometimes we also see spruce and fir in somewhat unexpected settings.

The picture above is an oblique, Google Earth view of a valley nestled between Umpire Mountain, Burke Mountain, and Kirby Ridge. The steepness of the terrain is exaggerated in this view. The Burke ski area is visible on the far side of Burke Mountain (center) while the spruce forest in the photo I posted earlier is on the far right of this view, on the steep slopes of Umpire Mountain. Not surprisingly, you can see lots of conifers on these tall mountains, where a lot of snow is also visible (the photo was taken in April of 2006).

You'll also notice something else here though. The conifers aren't restricted to the mountaintop. There are also a bunch of them in the valley. What gives?

Those spruce and fir trees are present in the valley bottom because of cold air drainage. Most of the time, the mountaintops are the coldest parts of Vermont. But, during a cold, still clear night, things change. Heat rapidly radiates away from the mountains, but as air cools, it sinks. Cold air is denser than warm air. Cold air from the mountains surrounding this little valley trickles down to the valley bottom, where it pools. This cold air is no joke. In fact, on a frigid night in 1933, the town of Bloomfield 18 miles to the northeast of this basin measured a low temperature of -50, tied with a more recent record in Maine for the coldest temperature ever recorded in New England. There aren't any weather stations in Victory Basin (the area described above) though, and I wouldn't be surprised if it was even colder there that night.

There aren't many trees that can stand up to -50 degree temperatures, but spruce is one of them. Together with fir and a few other species, the cold air pockets of New England and upstate New York support a natural community called Lowland Spruce-Fir Forest.

View Larger Map

The above map offers a view of Victory Basin, with the lowland spruce-fir forests and associated wetlands clearly visible (this is the same area where I saw a moose a few weeks ago). If you wander north on the above map you will notice a pattern of the darker green conifers being present both in the valleys and on the peaks. If you continue dragging the view north you will come to the Nulhegan Basin, an even larger cold-air drainage area. Both the Victory and Nulhegan basins support species similar to that in the boreal taigas in Canada, ranging from rhodora to the state endangered spruce grouse. Not surprisingly, moose are very abundant in these areas as well. Snowshoe hare and beaver are abundant, and it's possible that even lynx inhabit these icy forests.

Cold air drainage isn't limited to icy climates like Vermont's either. They play a part in the ecology and natural history of the sunny Santa Monica Mountains in Malibu, California as well. I've seen frozen ground and 'frost heaves' in this part of Malibu Creek State Park:

View Larger Map

This is just a few miles from the immediate coastline, where temperatures very rarely drop below 40F and hard freezes may only occur once or twice a century. Stephen Davis of Pepperdine University has found evidence that these cold air drainages strongly affect the vegetation in the area, and he has told me that single-digit (f) temperatures are not unheard of in these isolated areas. I believe it - one spring I lived in Park Service employee housing at nearby Rocky Oaks park, another cold air drainage area, and hard freezes were common on many clear nights well into April. I had to scrape the ice off of my car windshield in the mornings with a credit card because I didn't have an ice scraper. There were even areas of black ice on some of the nearby roads on cold nights after rainstorms.

Malibu's cold air pockets are more defined by an absence than a presence. The ubiquitous laurel sumac shrub that is found over almost all of the Santa Monica Mountains does not occur in cold air drainage areas. It is said that early farmers would only plant citrus where laurel sumac was growing, because it meant frost was very rare.

Next time you are in a small valley or hollow, look at the plants around you, because they may have an icy story to tell.

Above: on October 9th, a heavy frost settled over most of the Northeast Kingdom, but not Montpelier, Plainfield, or Barre. These little plants are bedstraw (Galium).

The early season frosts seem a bit random, but they are anything but. We can't "see" temperature changes, although we can notice where frost occurs on marginal freeze nights. There's another way to see the patterns of cold air too - and it is by observing where plants occur on the landscape.

above: red spruce on a talus slope.

Most people have noticed that conifers, like pine and spruce, often occur on cold mountaintops. In Vermont, the most cold-tolerant trees are spruce, fir, paper and yellow birch, and aspen. Of these, the hardwoods are opportunistic and occur in other areas as well, but spruce and fir are almost entirely restricted to areas that get very, very cold - like the steep talus slope high on Umpire Mountain, seen above. Sometimes we also see spruce and fir in somewhat unexpected settings.

The picture above is an oblique, Google Earth view of a valley nestled between Umpire Mountain, Burke Mountain, and Kirby Ridge. The steepness of the terrain is exaggerated in this view. The Burke ski area is visible on the far side of Burke Mountain (center) while the spruce forest in the photo I posted earlier is on the far right of this view, on the steep slopes of Umpire Mountain. Not surprisingly, you can see lots of conifers on these tall mountains, where a lot of snow is also visible (the photo was taken in April of 2006).

You'll also notice something else here though. The conifers aren't restricted to the mountaintop. There are also a bunch of them in the valley. What gives?

Those spruce and fir trees are present in the valley bottom because of cold air drainage. Most of the time, the mountaintops are the coldest parts of Vermont. But, during a cold, still clear night, things change. Heat rapidly radiates away from the mountains, but as air cools, it sinks. Cold air is denser than warm air. Cold air from the mountains surrounding this little valley trickles down to the valley bottom, where it pools. This cold air is no joke. In fact, on a frigid night in 1933, the town of Bloomfield 18 miles to the northeast of this basin measured a low temperature of -50, tied with a more recent record in Maine for the coldest temperature ever recorded in New England. There aren't any weather stations in Victory Basin (the area described above) though, and I wouldn't be surprised if it was even colder there that night.

There aren't many trees that can stand up to -50 degree temperatures, but spruce is one of them. Together with fir and a few other species, the cold air pockets of New England and upstate New York support a natural community called Lowland Spruce-Fir Forest.

View Larger Map

The above map offers a view of Victory Basin, with the lowland spruce-fir forests and associated wetlands clearly visible (this is the same area where I saw a moose a few weeks ago). If you wander north on the above map you will notice a pattern of the darker green conifers being present both in the valleys and on the peaks. If you continue dragging the view north you will come to the Nulhegan Basin, an even larger cold-air drainage area. Both the Victory and Nulhegan basins support species similar to that in the boreal taigas in Canada, ranging from rhodora to the state endangered spruce grouse. Not surprisingly, moose are very abundant in these areas as well. Snowshoe hare and beaver are abundant, and it's possible that even lynx inhabit these icy forests.

Cold air drainage isn't limited to icy climates like Vermont's either. They play a part in the ecology and natural history of the sunny Santa Monica Mountains in Malibu, California as well. I've seen frozen ground and 'frost heaves' in this part of Malibu Creek State Park:

View Larger Map

This is just a few miles from the immediate coastline, where temperatures very rarely drop below 40F and hard freezes may only occur once or twice a century. Stephen Davis of Pepperdine University has found evidence that these cold air drainages strongly affect the vegetation in the area, and he has told me that single-digit (f) temperatures are not unheard of in these isolated areas. I believe it - one spring I lived in Park Service employee housing at nearby Rocky Oaks park, another cold air drainage area, and hard freezes were common on many clear nights well into April. I had to scrape the ice off of my car windshield in the mornings with a credit card because I didn't have an ice scraper. There were even areas of black ice on some of the nearby roads on cold nights after rainstorms.

Malibu's cold air pockets are more defined by an absence than a presence. The ubiquitous laurel sumac shrub that is found over almost all of the Santa Monica Mountains does not occur in cold air drainage areas. It is said that early farmers would only plant citrus where laurel sumac was growing, because it meant frost was very rare.

Next time you are in a small valley or hollow, look at the plants around you, because they may have an icy story to tell.

Monday, October 8, 2012

Water and Rivers on Other Worlds

An incredible discovery was made recently by the Curiosity rover on Mars, that was a bit overshadowed at the time by politics and other news. Smooth pebbles were found on an alluvial fan in Gale Crater. These pebbles are evidence of water flowing over the surface of Mars for extended periods of time.

(all photos here courtesy of NASA and JPL).

We've known for a long time that Mars has water ice on it and at one time almost certainly supported liquid water. It may have small, short-lived trickles of salty water in a few places even today. The pebbles show us something else, though. The pebbles, which appear to be scattered over a large alluvial fan, show us evidence of a river or stream on Mars that probably flowed for thousands or millions of years.

Above: more outcroppings containing water-deposited pebbles)

This doesn't mean there was continuous flow in this watercourse. Mars was likely drier than Earth even back then. The alluvial fan looks a lot like those found in very dry deserts on Earth such as Death Valley and the Atacama Desert:

In those deserts the dry washes can go years or even decades between seeing any surface flow of water. When it does come, though, the dry soils, exposed rock, and sparse vegetation mean that a thunderstorm can unleash massive flash floods. The same could have been true on Mars. We don't know of any vegetation that ever existed on Mars, so it's quite possible that the flash floods would have been even more severe than on Earth, though perhaps slower-moving due to the lower gravity. Then again, Mars could have also supported some tough, hardy life similar to that which occurs in Death Valley today. We won't ever know unless we find evidence of that life, because we can't disprove that it was there by NOT finding fossils or other evidence.

Dry washes prone to flash floods are not easy places to live, but the wash probably emptied into a lake similar to those in the Great Basin today. Perhaps it was a usually-dry lake like Amargosa Dry Lake in Death Valley or perhaps it contained significant amounts of salty water all the time, like Mono Lake in the Eastern Sierras.

Most washes in even the driest deserts also have a few spots of moisture. Upstream from the alluvial fan, in a steep gorge, often near a dry waterfall, there are places where bedrock forces the scant groundwater to the surface. On Earth, these little seeps are tiny islands of life in the desert, and often support a few weathered trees such as cottonwoods. The seeps are, of course, also vital to desert animals looking for water. Whether or not Mars ever held life, there apparently were dynamic watersheds, springs, ponds, rivers, canyons, flood plains, and other water features found all over Earth.

Water is an incredibly common compound throughout the universe, and with billions of planets (and countless moons around those planets too), there are certainly untold trillions of rivers flowing on other worlds. With all those planets it seems certain there must be other life out there too, maybe quite a bit of it.

One of the most bizarre recent findings from space is that rivers need not always contain water. On Titan, which is much, much colder than Earth but does support a thick atmosphere, there are many active rivers, but of methane, not water. Perhaps even more mind-bogglingly, the rock that these rivers erode through consists primarily of water ice!

The above air photo is from the Cassini-Huygens space probe.

A Google image search for Titan Rivers will bring up a vast number of incredible photos of river systems and lakes or oceans on Titan. Interestingly these images reveal a relatively young landscape - the rivers look to be young and very active, and few impact craters are evident. It seems that Titan in fact is covered in a very extensive network of tributaries and rivers, much like Earth. Unlike those on Mars, these are still very much active. And, they can't really be called watersheds - more accurately they are 'methanesheds'.

Conversely, there are probably very hot planets where rock flows in rivers as lava, through some other substance, and water exists only as a gas? Venus is very hot and may experience some sort of drizzle, but no evidence of 'watersheds' created by other flowing liquids.

We are surrounded by incredible wonder and diversity in our universe, but the fact remains that despite all these rivers on other worlds, we are utterly dependent on our own rivers and water for our survival. We are, of course, all on one tiny planet amidst all this wonder, and for the time being unable to leave. Even if we do, Earth will always be 'home'. We need to take care of our rivers.

(all photos here courtesy of NASA and JPL).

We've known for a long time that Mars has water ice on it and at one time almost certainly supported liquid water. It may have small, short-lived trickles of salty water in a few places even today. The pebbles show us something else, though. The pebbles, which appear to be scattered over a large alluvial fan, show us evidence of a river or stream on Mars that probably flowed for thousands or millions of years.

Above: more outcroppings containing water-deposited pebbles)

This doesn't mean there was continuous flow in this watercourse. Mars was likely drier than Earth even back then. The alluvial fan looks a lot like those found in very dry deserts on Earth such as Death Valley and the Atacama Desert:

In those deserts the dry washes can go years or even decades between seeing any surface flow of water. When it does come, though, the dry soils, exposed rock, and sparse vegetation mean that a thunderstorm can unleash massive flash floods. The same could have been true on Mars. We don't know of any vegetation that ever existed on Mars, so it's quite possible that the flash floods would have been even more severe than on Earth, though perhaps slower-moving due to the lower gravity. Then again, Mars could have also supported some tough, hardy life similar to that which occurs in Death Valley today. We won't ever know unless we find evidence of that life, because we can't disprove that it was there by NOT finding fossils or other evidence.

Dry washes prone to flash floods are not easy places to live, but the wash probably emptied into a lake similar to those in the Great Basin today. Perhaps it was a usually-dry lake like Amargosa Dry Lake in Death Valley or perhaps it contained significant amounts of salty water all the time, like Mono Lake in the Eastern Sierras.

Most washes in even the driest deserts also have a few spots of moisture. Upstream from the alluvial fan, in a steep gorge, often near a dry waterfall, there are places where bedrock forces the scant groundwater to the surface. On Earth, these little seeps are tiny islands of life in the desert, and often support a few weathered trees such as cottonwoods. The seeps are, of course, also vital to desert animals looking for water. Whether or not Mars ever held life, there apparently were dynamic watersheds, springs, ponds, rivers, canyons, flood plains, and other water features found all over Earth.

Water is an incredibly common compound throughout the universe, and with billions of planets (and countless moons around those planets too), there are certainly untold trillions of rivers flowing on other worlds. With all those planets it seems certain there must be other life out there too, maybe quite a bit of it.

One of the most bizarre recent findings from space is that rivers need not always contain water. On Titan, which is much, much colder than Earth but does support a thick atmosphere, there are many active rivers, but of methane, not water. Perhaps even more mind-bogglingly, the rock that these rivers erode through consists primarily of water ice!

The above air photo is from the Cassini-Huygens space probe.

A Google image search for Titan Rivers will bring up a vast number of incredible photos of river systems and lakes or oceans on Titan. Interestingly these images reveal a relatively young landscape - the rivers look to be young and very active, and few impact craters are evident. It seems that Titan in fact is covered in a very extensive network of tributaries and rivers, much like Earth. Unlike those on Mars, these are still very much active. And, they can't really be called watersheds - more accurately they are 'methanesheds'.

Conversely, there are probably very hot planets where rock flows in rivers as lava, through some other substance, and water exists only as a gas? Venus is very hot and may experience some sort of drizzle, but no evidence of 'watersheds' created by other flowing liquids.

We are surrounded by incredible wonder and diversity in our universe, but the fact remains that despite all these rivers on other worlds, we are utterly dependent on our own rivers and water for our survival. We are, of course, all on one tiny planet amidst all this wonder, and for the time being unable to leave. Even if we do, Earth will always be 'home'. We need to take care of our rivers.

Monday, October 1, 2012

New Iphone 5 and Gratuitous Vermont Fall Foliage

My phone recently died, giving me an excuse to upgrade to an iPhone 5. This post is ostensively a review of the new iPhone 5, but is really just an excuse to post beautiful fall foliage photos.

The iPhone 5 camera seems fairly similar to its predecessor, at least to someone who isn't an expert in photography. However, there are a few new features. First of all, photos snap a lot quicker, which is nice for taking photos of things seen from a moving vehicle.

Note: don't be a distracted driver! Have the passenger take the photos.

There's also a HDR feature - which existed in the iPhone 4 also, and allows for brighter colors and a more even exposure. It can also lead to 'fake' looking photos with exaggerated color.. But, in the case of Vermont fall foliage, the colors are always vastly more vivid than I'm able to capture in a photo, and the HDR gives a somewhat better representation of that.

This was an HDR photo - note the vivid colors but also the 'ghost' trees on the horizon.

The HDR can cause weird photo 'artifacts' when photographing fast-moving objects, because it really takes a compilation of several photos.

Perhaps the funnest new feature is the panorama feature which allows the creation of a 180 degree panorama (vertical or horizontal) without using an external app. It works great. Click on the photo below for a larger view of a foot, horse, and snowmobile bridge across the Moose River:

This bridge is at the point where the river flows out of the Victory Basin.

Looking downstream, the river is a typical beautiful Vermont river, with riffles and pools:

Looking upstream, the alder swamps and black cherry floodplain woodlands are visible in the distance:

The maples are vividly red, especially the well-named red maples, and the birch are a striking shade of yellow.

Some may disagree but I find that a drizzly, dark day like today really brings out hte fall foliage. Though, to be fair, the sun through the yellow birch leaves is also amazing. The beech trees are still green.

Oh yeah.. I almost forgot about the iPhone. In short, people who are very into the art of photography will not want to use the iPhone as their primary camera, but for people like me more interested in easily being able to take photos for outreach or science, it works great.

For more fall foliage photos click here. I'll be updating this as the season goes on.

Oh yes, one other thing... it's advisable to avoid using the iPhone 5 maps for directions in rural areas. Vermont isn't as hazardous as the desert, except in a blizzard perhaps, but if you want to explore the backroads of the Northeast Kingdom of Vermont, where the foliage is near peak right now, bring a paper map and better yet enquire locally at any store or info center. People love sharing their favorite roads and places. Even more so in the winter... iPhone maps and even Google Maps often don't 'know' that many roads are closed in the winter or require 4*4 (or a snowmobile).

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)